- History

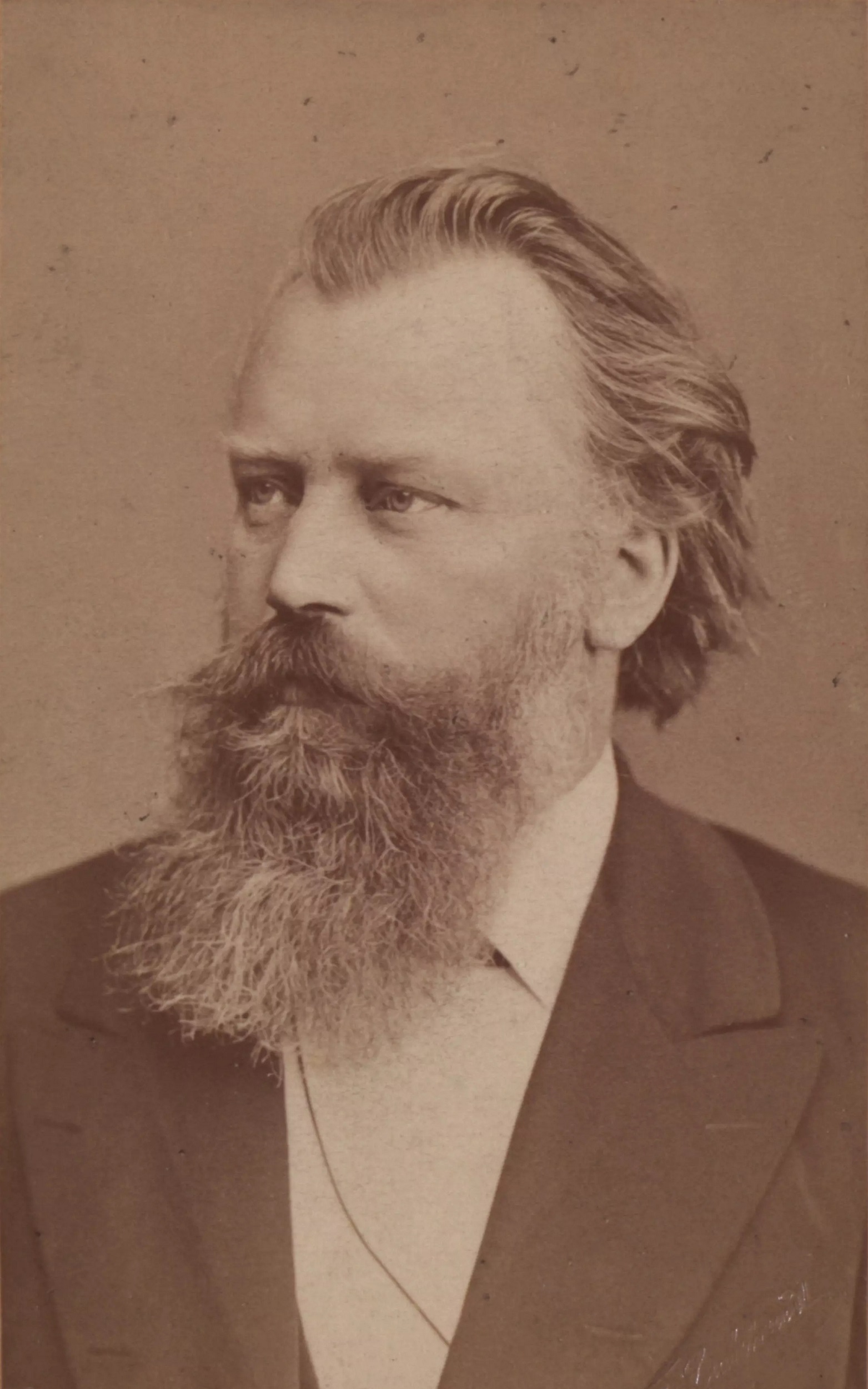

Without the violinist Joseph Joachim, Brahms would probably never have written his Violin Concerto. The work is the result and the expression of a long-standing friendship. Joachim paved the way for Brahms’s artistic career, and welcomed him into his professional network. The two regarded each other as brothers in spirit – until a bitter divorce nearly destroyed everything.

In 1899, two years after Johannes Brahms’s death, the first monument was erected to him – in Meiningen, since the composer had maintained a good relationship with the court orchestra there. Brahms outlived almost all of his well-known peers. But one of his oldest friends, musical partners and promoters now stood in the shadow of the monumental bust, which had just been unveiled, and gave a euology. “I have stood close to this great artist longer than anyone else in this circle, for almost half a century,” declared Joseph Joachim, the most celebrated violinist of his day.

Their paths crossed for the first time in 1848, in Brahms’s native city of Hamburg. The 15-year-old Brahms was awestruck when he heard Joachim, who was only two years older, play Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. Establishing contact with him was out of the question; after all, the violinist was already a celebrity at the time. Born in the Austro-Hungarian territory of Burgenland in 1831, he had appeared as a child prodigy at the age of seven. Together with his mentor Felix Mendelssohn, he rediscovered Beethoven’s long-forgotten Violin Concerto and also introduced Beethoven’s string quartets to a wider audience with his own ensemble. He embodied an entirely new type of musician: not a self-promoting devil’s violinist like Paganini, not a narcissistic virtuoso, but a conscientious interpreter who put his high technical level at the service of the composer (as we can hear today on crackling waltz recordings).

Meeting each other personally

They met in person five years later. In 1853 Brahms came to Hanover, where Joachim was then concertmaster of the court orchestra, on a tour as accompanist to the Hungarian violinist Eduard Reményi. Although Brahms was still a newcomer, the two immediately recognized each other as brothers in spirit. “I have never before come across so great a talent,” Joachim enthused. “His playing shows an intense fire and the energy and precision which bodes well for the artist, and his compositions already bespeak such power as I have seen in no other musician of his age.” When Reményi suddenly left Brahms in the lurch shortly afterwards, the path was clear for a personal and musical partnership that would go down in musical history.

The two played innumerable concerts together over the next decades – as a chamber music duo, or with Brahms conducting and Joachim as soloist. Occasionally they argued, half serious, half teasing, about whose name should appear first on the posters. They wrote around 500 letters to each other, the at times humorous tone of which is reflected in salutations such as “My dear Jussuf”. In them, Brahms frequently asked for compositional advice – he even proposed that they exchange exercises in counterpoint every fourteen days “until we have both become really clever”. Whoever was too late had to pay into a “penalty box” from which the other could buy books. Lines such as these reveal how much he valued this exchange: “Your letter made me quite excited with joy, my dear Joseph. I had to run outdoors, because I didn’t want to jump for joy inside.”

A personal and musical friendship

Above all, however, Brahms used his older friend to open doors for him. He asked Joachim to “introduce him to artistic life”, and Joachim was happy to help. On his recommendation, Brahms established contacts with concert managers and publishers, and introduced himself to Franz Liszt and the Schumanns. His visit to Düsseldorf was topped off with Robert Schumann’s prophetic newspaper article, which praised the young composer as the “Messiah of new music”.

He also contributed to a collaborative composition, the “F-A-E Sonata”, alluding to Joachim’s motto “Frei, aber einsam” (Free but lonely), which Brahms immediately adopted for himself – and firmly adhered to, as a perennial bachelor himself. In addition, he composed musical birthday gifts, such as a waltz with the ironically pretentious title Hymn in Honour of the Great Joachim. Still, the violinist had to wait for a long time for a substantial work by his composer friend,.

The break

Not until 25 years later did Brahms send sketches for a violin concerto which he dedicated to Joachim. “It was my intention, of course, that you should correct it,” he wrote in 1878. “I shall be satisfied if you will mark those parts which are difficult, awkward or impossible to play.” Joachim’s answer came promptly: “I have had a good look at what you sent me and have made a few notes and alterations. I can, however, make out most of it, and there is a lot of really good violin music in it.” In spite of his understatement, he proposed numerous alterations – which did not mean that Brahms adopted all of them.

The break came unexpectedly in the early 1880s. Joachim became convinced that his wife Amalie – a prominent contralto, for whom Brahms composed several songs – was having an affair with the publisher Fritz Simrock. In the ensuing marital dispute, Brahms sided with Amalie: “Dear Friend, Your letter made me genuinely sad. A really serious reason [= an affair] is difficult to imagine and probably does not exist.” When Amalie produced a (confidential) letter from Brahms during the divorce proceedings in which he described Joachim’s excessive jealousy as an “unfortunate character trait”, the scandal was complete, and the friendship destroyed.

A double concerto as a gesture of reconciliation

After years of silence, Brahms composed his Double Concerto for Violin and Cello as a gesture of reconciliation in 1887. “Prepare yourself for a little shock,” he wrote to Joachim. “I ask you in all sincerity and friendliness not to be in the least embarrassed. If you’ll send me a postcard which simply says: ‘I decline’, I’ll know enough and how to fill in the rest myself.” Fortunately, Joachim accepted the peace offering; at the premiere of the Double Concerto the two finally stood on the stage together again. The following year, Brahms even added another violin sonata. Did all of this cross Joseph Joachim’s mind as he remembered the composer at the unveiling of the Brahms monument in Meiningen? One thing is certain: without their friendship, music history and the concert repertoire would be much poorer.

Between heaven and earth

Johannes Brahms and the Berliner Philharmoniker share a special history. We take a deeper look at his “Song of Destiny”.

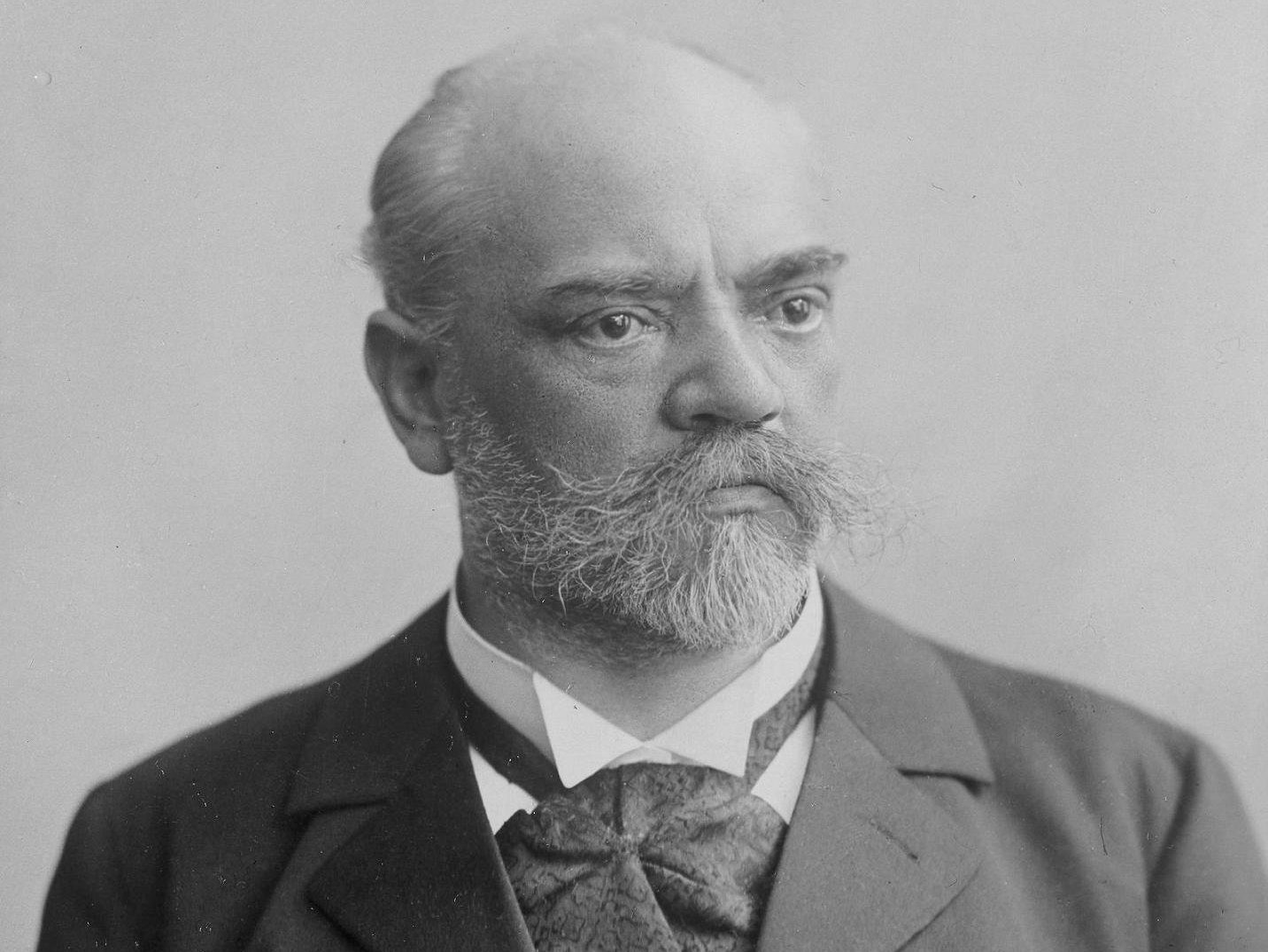

Dvořák’s path to fame

From orchestral musician to national composer – Antonín Dvořák had an unprecedented career. Thanks to his musical genius and his mentor.

Georg Schumann and the Berliner Philharmoniker

The musical partnership with conductor, pianist and composer Georg Schumann lasted over six decades.