- History

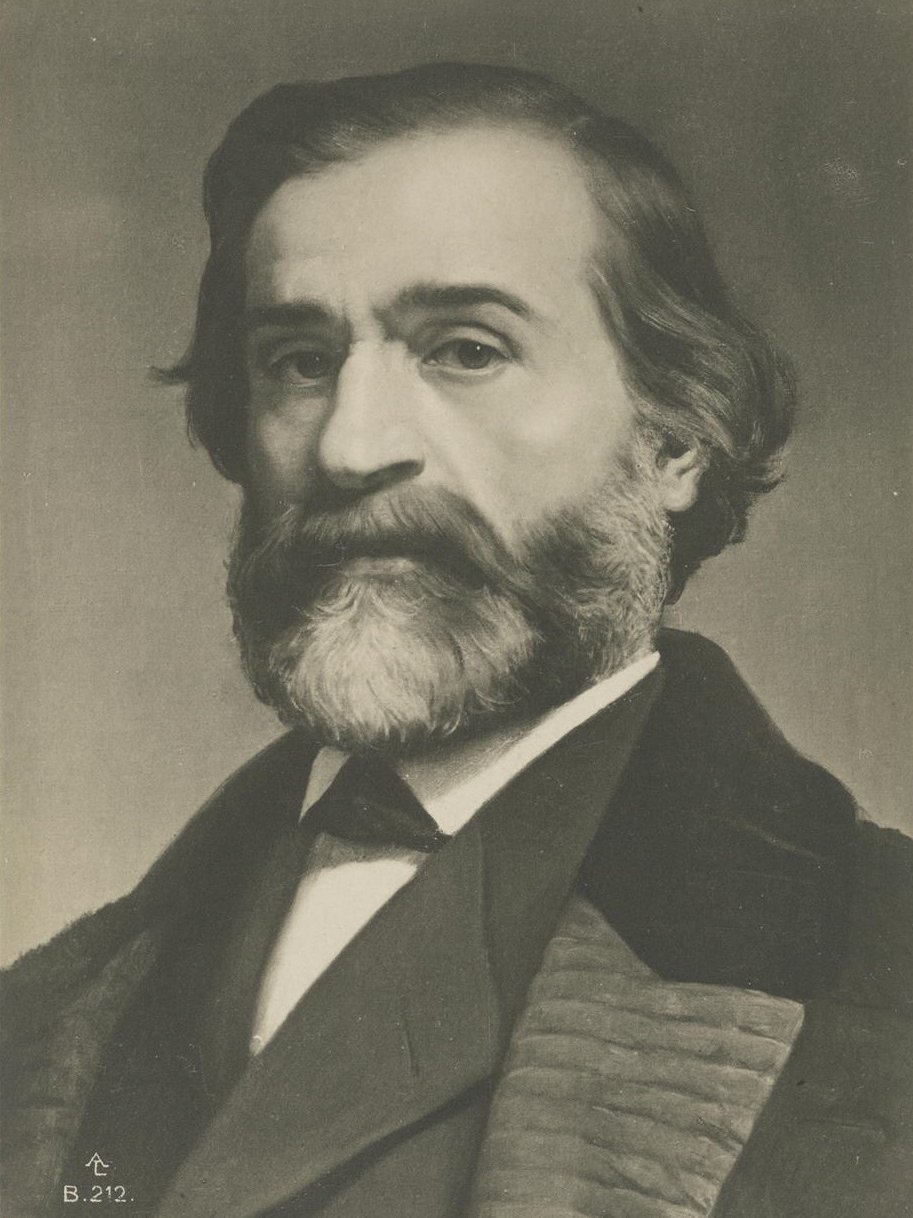

You can hum along to “La donna è mobile” in your sleep, and you know of course that Aida, Rigoletto and Nabucco are not varieties of Italian grapes. But did you know that the world-famous opera composer Giuseppe Verdi was also a vintner, a member of parliament and a keen foodie? We have found out little-known facets and facts about the composer.

1. “I don't know whether the quartet is beautiful or not, but I know that it is a quartet.”

It was only at the age of 60 that Verdi wrote his first ever string quartet; supposedly out of boredom because he had to pause his work on Aida. His only string quartet was written in a hotel room in Naples, although he was actually convinced that instrumental music was a “thing of the Germans and the string quartet a plant that is not suited to the Italian climate”. Nevertheless, he presented his work on the evening of 1 April 1873 (as an April Fool's joke?) at a dinner for friends, who he nevertheless coyly asked not to fall asleep. But when it was over, the guests even demanded the piece be repeated. Verdi stated: “I don’t know whether the quartet is beautiful or not, but I know that it is a quartet.” Minimum requirement fulfilled.

2. Fateful blows and a flop

The music world was almost poorer by numerous operatic masterpieces and catchy tunes. In his 30s, Verdi fell into a depression after his beloved wife Margherita and his two small children all died within two years. When his opera Un giorno di regno flopped, he reportedly vowed never to compose again. Theatre manager and librettist Bartolomeo Merelli, however, managed to change his mind. Verdi’s first world hit followed: Nabucco.

3. Verdi vs. Wagner

Aida almost didn’t come to anything either: Verdi initially turned down the commission for an opera based on the story of the Ethiopian king's daughter. Only when he discovered that the work would be offered to Richard Wagner did he accept. Although they were the most influential opera composers of their time and never met in person, Verdi and Wagner cultivated a certain dislike for each other. Verdi said of his rival: “He always, unnecessarily, chooses the untrodden path, tries to fly where a reasonable man would walk with better results.”

4. Giuseppe and Giuseppina

In 1839 Verdi met the extremely successful opera singer Giuseppina Strepponi, who was already financially independent enough at the time to finance the education of her three siblings and support her mother.

The two initially lived together in Paris and Italy, but later married. The union had its crises not least due to what was probably not just a platonic relationship between Verdi and the prima donna Teresa Stolz. A reconciliation finally took place while Verdi was working on Otello (his penultimate opera).

Giuseppina proved to be a dependable partner and negotiated for her husband in London, for example. The Hungarian writer Dezső Szomori said of a meeting with the Verdis in 1894: “A beautiful and charming couple who have grown old together in the world of music”.

5. Verdi, the politician

Verdi’s operas can certainly be interpreted politically – which many contemporaries did. Accordingly, the censors regularly tried to intervene in his works. But to this day, it cannot be proven conclusively how much Verdi was actually interested in politics. Nevertheless in 1861, he was elected as a deputy to the new Italian parliament in Turin, where he served until 1865.

6. Viva Verdi

The name Verdi was nevertheless political: in the years of the Risorgimento, the Italian unification movement, it was even used as a cipher. “Viva Verdi” was translated as “Viva Vittorio Emanuele Re d’Italia” (“Long live Vittorio Emanuele, King of Italy”). Vittorio Emanuele II, King of Sardinia-Piedmont at the time, became the figurehead of the unification movement. With this slogan, supporters could pay homage to the king.

7. The farmer of St. Agata

Verdi liked to flirt with the fact that he was actually an “opera farmer” and preferred the simple country life. After his first financial successes, he built the Villa Sant’Agata near his birthplace where he devoted himself to farming: he bred horses, planted vines and had ponds built in the shape of his initials G and V, which still exist today.

8. Verdi, the foodie

The world-famous composer Verdi was apparently what we today would call a foodie. In numerous letters he wrote about his passion for food, gave cooking tips, talked about recipes and anecdotes from the kitchen. He sent hams and cheeses to friends as a kind of ambassador for his region and organised lunches at his villa. His speciality was apparently risotto alla Milanese.

9. Casa Verdi

“Among my works that I like best is the house I built in Milan to house elderly singers.” In 1889, Verdi commissioned the construction of a retirement home for poor musicians. At around the age of 50, Verdi himself was so financially independent that he was in a position to retire. Since he could apparently remember different times, he became very socially involved and organised meals for the poor. Incidentally, his retirement home, the Casa Verdi, still houses artists and musicians today.

11 Facts about the Viennese Waltz

A compact guide to the waltz for the concert interval

Schoenberg revealed

Arnold Schoenberg was one of the most important composers of the 20th century. In addition to his work as a composer, Schoenberg was also a painter, an inventor and a theoretician.

Maurice Ravel’s “Boléro”: 7 facts about the world-famous work

A masterpiece, “unfortunately without music” was Ravel’s own judgement of his work. Discover 7 entertaining facts about the piece.