- History

Composers, writers, artists and other intellectuals who had fled from the National Socialists came together in Los Angeles in the 1940s. Not only Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto was written there, but also Thomas Mann’s novel Doctor Faustus. Franz Werfel and his wife Alma Mahler-Werfel, Erich Korngold, Alexander Zemlinsky, Bruno Walter, Kurt Weill, Theodor W. Adorno and many others also found refuge in the US – often under precarious economic conditions, however.

The cultural elite of Germany and Austria suffered forced personal and artistic uprooting during the 1930s and 40s after the National Socialists seized power. The extent of the persecution was so unthinkable that only a few artists set out on the journey into exile as early as Arnold Schoenberg. Many hesitated a long time – too long to be able to escape arrest and murder. Schoenberg had already emigrated from Le Havre to New York with his family in October of 1933, after the National Socialists had revoked his professorship at the Berlin Academy of the Arts. Joseph Malkin, the former principal cellist of the Berliner Philharmoniker, initially provided Schoenberg with a source of livelihood in the US. Malkin had lived in Boston for a long time and offered him a teaching position at his private conservatory. Schoenberg soon took up residence in Los Angeles, where his material existence was secured with a professorship.

Schoenberg in Hollywood’s neighbourhood

Along with California’s sunny sides, the occasional cocktail parties and legendary tennis matches with his neighbour George Gershwin, one should not forget, however, that Schoenberg by no means led a life of luxury among Hollywood stars. Despite his constant shortage of money, out of self-esteem he demanded very high fees, also for his Piano Concerto, composed in 1942. And he made a distinction between what was financially necessary and what was artistically justifiable in its own right. Advances by the film producer Irving Thalberg on behalf of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios came to nothing in 1935 as a result of Schoenberg’s uncompromising attitude. In spite of this attempt by Hollywood, Schoenberg’s music was little known in the US, which troubled him as much as the unfamiliar language (although he soon eliminated the umlaut in his name in favour of “oe”, which was easier to understand in American English).

Schoenberg was not the only artist confronted with this lack of response. Almost all the emigrants found that they were not able to seamlessly pick up the threads of their former prominence in the New World, and English was not as widespread, either as an academic language or in everyday use, in those days as it is today. Many compensated for the traumatic loss of their intellectual home with a demonstrative display of cultural superiority. Moreover, the community of refugees stranded on California’s west coast by no means proved to be a solidly united group. Naturally they sent each other gestures of help and support, but amid the enormous psychological strain of the everyday struggle for existence, there were rivalries, envy and intrigues as well as social contact out of pure courtesy, like that cultivated by Schoenberg and Thomas Mann, who moved into the neighbourhood in 1941.

They did not become friends. Schoenberg’s daughter Nuria Nono-Schoenberg, now 90 years old, recalls the stiff visits: “Once we were invited to the Manns in Los Angeles, around the beginning of the 1940s, and I had to stay outside in the garden while the adults conversed inside.” The fact that Mann was working his novel Doctor Faustus at the time and capitalized on the theory of the twelve-tone technique without informing Schoenberg enraged the composer.

The German exile scene gathered around Alma Mahler-Werfe

After retiring from his teaching post because of his age and drawing only a meagre pension, Schoenberg found himself facing serious financial problems in 1944. “Arnold Schoenberg is starving,” Alma Mahler-Werfel wrote in her diary. She and her husband, the writer Franz Werfel, had also escaped from Europe under extremely difficult circumstances and had taken up quarters in California. Alma Mahler-Werfel made her changing residences in Los Angeles the meeting places of the German exile scene. Thomas and Heinrich Mann with their wives Katia and Nelly were invited to dinner, as well as Erich Wolfgang Korngold and his wife Luzi or Bruno Walter and his secret lover Erika Mann. “Erika’s regrettable overdoing it with alcohol (with Mahler),” Thomas Mann noted in his diary, disgusted with his daughter. Alma Mahler-Werfel would later play an important role as a mediator in the ugly dispute between Schoenberg and Mann.

The comparatively comfortable financial situation of the Werfels was due above all to his international best-sellers and lucrative film rights. Erich Wolfgang Korngold also suffered no material hardship in exile. He had already taken up director Max Reinhardt’s invitation to Hollywood in 1934 and had built a brilliant career as a film score composer. Korngold was cheated out of the financial and intangible income from his operas in Europe, however. He, who had once dominated German programmes with his Tote Stadt, had to realize, embittered, that people no longer took him seriously as a composer. Korngold’s attempt to become established again in his native Vienna after the war failed miserably – he was even accused of living the high life in Hollywood while those left behind lived in ruins.

Uprooting with grave consequences

Arnold Schoenberg’s friend and former brother-in-law Alexander von Zemlinsky was also a frequently performed opera composer until the annexation of Austria drove him and his wife Louise into exile. The Zemlinskys were stranded in New York, financially depleted and psychologically broken. Zemlinsky survived this uprooting less than four years. Jaromír Weinberger, the composer of the acclaimed opera Schwanda the Bagpiper, endured it several years longer. He had also fled in 1938 and at first kept afloat financially with small commissions until poverty, depression and the fate of his family, who were killed in the Holocaust, cast a shadow over his existence. Weinberger took his own life in 1967.

Only a few succeeded in reinventing themselves. One of them was Franz Wachsmann, who soon called himself Waxman and attracted attention in Hollywood with sophisticated, Oscar-winning film scores. Kurt Weill, on the other hand, established himself with musicals on Broadway. Weill’s successes were inextricably linked with his wife Lotte Lenya, an actress and singer, who had emigrated to New York with him in 1935. Lotte Lenya was a good networker and wrote to her husband: “If you have time to see this Wiesengrund [Theodor W. Adorno, who had also emigrated], you should do so. That one always has such good connections to the genteel, delicate aroma. And he does beat the drums for you a bit – that is, when he’s not too busy praising his own immortal creations.”

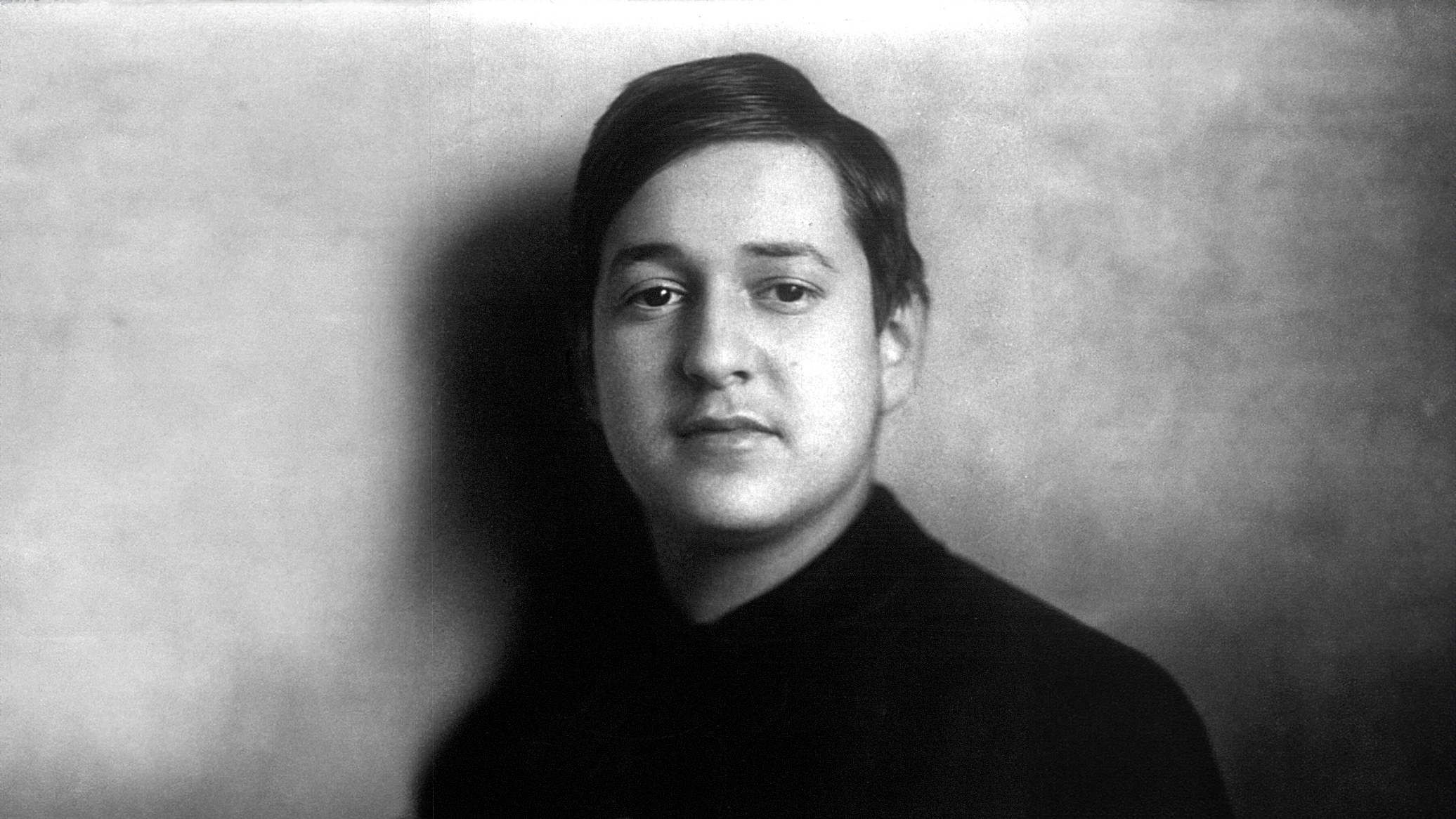

Schoenberg revealed

Arnold Schoenberg was one of the most important composers of the 20th century. In addition to his work as a composer, Schoenberg was also a painter, an inventor and a theoretician.

Gustav and Alma Mahler

Should she really accept his offer of marriage? At twenty-two, Alma was an extraordinarily beautiful and charismatic woman. Mahler was a social climber from the provinces.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

In the 1920s, Korngold was one of the most frequently performed opera composers of the time. The Nazi regime forced him to emigrate to the USA, where he embarked on a second career.