On 6 June 2025 between 9 and 14:30, the subscription office is not available via phone or in person. Thank you for your understanding.

- Portrait

Gustav Holst was a modest man who accepted success rather than striving for it. Even so, he refused to compromise when it came to implementing his artistic ideals.

“If one is lucky (or maybe unlucky – it doesn’t matter) to have a clearly appointed path to which one comes naturally whereas any other one is an unsuccessful effort, one ought to stick to the former.” Holst formulated this article of faith in a letter that he wrote in 1926 to his lifelong friend and fellow composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. It was inspired by the idea of dharma, one of the keys concepts of Hindu ethics, which places our quest for wisdom at the very centre of our lives. Ideally, this quest should be divested all of vanity and all egoism. Against this background, all of the things that normally matter in the world – power, money and fame – lose their significance.

As an aspiring composer, Holst had to earn his living playing the trombone with the Carl Rosa Opera Company, and later the Scottish Orchestra. He first came into contact with Sanskrit literature in 1899 and quickly made up his mind to set a series of texts from the Ramayana, India’s national epic, to music. But when he inquired about translations at the British Library in London, he found the material unusable. He enrolled in a course in Sanskrit at University College, London, learnt the alphabet, and made enough progress to be able to decipher the original texts sentence by sentence with the help of a dictionary.

Inspired by Indian culture

Over the years Holst’s engagement with Indian culture led to the creation of an impressive body of disparate works, including four sets of Choral Hymns from the Rig Veda, the cantata The Cloud Messenger, a symphonic poem with the title Indra and two works of music theatre. His chamber opera Sāvitri has retained a place for itself in the repertory, unlike his large-scale opera Sita, which no theatre was willing to stage during Holst’s own lifetime and which did not receive its world premiere until October 2024, when a production was mounted in Saarbrücken to mark the 150th anniversary of its composer’s birth.

Gustav Holst was born in Cheltenham on 21 September 1874. No matter what he turned his hand to, he did it thoroughly. Although he was a permanently sickly child who suffered from asthma and myopia, his ability to play the piano, the violin and the trombone earned him the respect of his classmates; at London’s Royal College of Music, he impressed his teachers with his single-mindedness and integrity.

A committed teacher with a great love of life

Holst was unable to make ends meet through his work as a composer, but whatever jobs he may have been forced to take on in order to earn his living, he always carried them out extremely conscientiously. Between 1898 and 1903 his commitments as a trombonist allowed him to learn the art of orchestration, after which he found work as a music teacher at two girls’ schools in London as well as at Morley College for Working Men and Women, a pioneering adult-education establishment. A committed teacher, he was dissatisfied with the teaching materials that were in use at that time and wrote a number of choral and orchestral works for pedagogical purposes, while at the same time always trying to encourage his charges to express their own independent creativity.

Many people, he complained, prescribed music for children as if it were some kind of medicine that was said to be good for them. Far more important than merely passing on knowledge, he argued, was creativity; all children, he was convinced, had an instinct for composition. Wherever possible, the works that they wrote simply for the pleasure of expressing themselves should be performed in public.

The touchstone of success, Holst believed, was the artistic enjoyment felt when performing, writing and hearing music. In 1911, he even mounted a performance of Purcell’s semi-opera The Fairy Queen with his students at Morley College, the first time that this Baroque masterpiece had been heard since 1692. Performed in London’s Royal Victoria Hall, it was based on parts laboriously prepared by the students, who copied it out over a period of eighteen months.

An approachable man with a sense of humour

Holst’s friends valued him as an approachable, sociable person with a great sense of humour and an astonishingly loud laugh. But he did not enjoy appearing in public, and hated acclaim, so suspicious was he of success: “If nobody likes your work,” he is alleged to have said, “you have to go on just for the sake of the work. And you’re in no danger of letting the public make you repeat yourself.” Holst stuck to this maxim even after his orchestral suite The Planets had turned out to be an international success.

The Planets was such a success that it brought him royalties and recognition, while the novel sonorities that he used to evoke outer space were to inspire countless later film composers. Despite this, he did not write a sequel to The Planets, turning instead to other fields of interest, even going so far as to strike out in diametrically opposite directions with many of his other projects.

A hit followed by a lot of misunderstanding

Holst went on to write The Hymn of Jesus; Egdon Heath, an orchestral suite inspired by Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native; a Double Concerto for two violins and orchestra; and a Choral Symphony, an austere but discursive setting of poems by John Keats that left even Holst’s closest friend, Vaughan Williams, unimpressed. Public and press alike reacted to Holst’s later operas with an almost total lack of understanding: these operas include At the Boar’s Head, a setting of the Falstaff scenes from Shakespeare’s Henry IV; The Wandering Scholar, a chamber opera set in the Middle Ages; and The Perfect Fool, a parody of Wagner and Verdi.

In 1932 Holst received an invitation from Harvard University to be visiting lecturer in composition, an invitation that he was pleased to accept not least because the Boston Symphony Orchestra offered to mount a series of concerts featuring some of his compositions under his own direction. The appointment was intended to last for six months, but after only three Holst was taken ill with a duodenal ulcer, and was forced to return home. On his return to England, Holst spent eighteen months in and out of hospital before he finally agreed to a risky operation in May 1934. Although the operation was a success, he died of heart failure only two days later.

Holst’s great-grandfather, grandfather and father had all been professional musicians, while his only daughter Imogen was the first woman to take over the baton as a member of the fifth generation. She was active as a pianist and as a conductor, as well as being a composer in her own right. She also worked closely with amateur musicians, and in 1938 published a biography of her father. For decades, she was also the artistic director of Benjamin Britten’s Aldeburgh Festival, and was highly regarded as a teacher. But she remained single by choice, and never had children; with her death in 1984, the Holst dynasty came to an end.

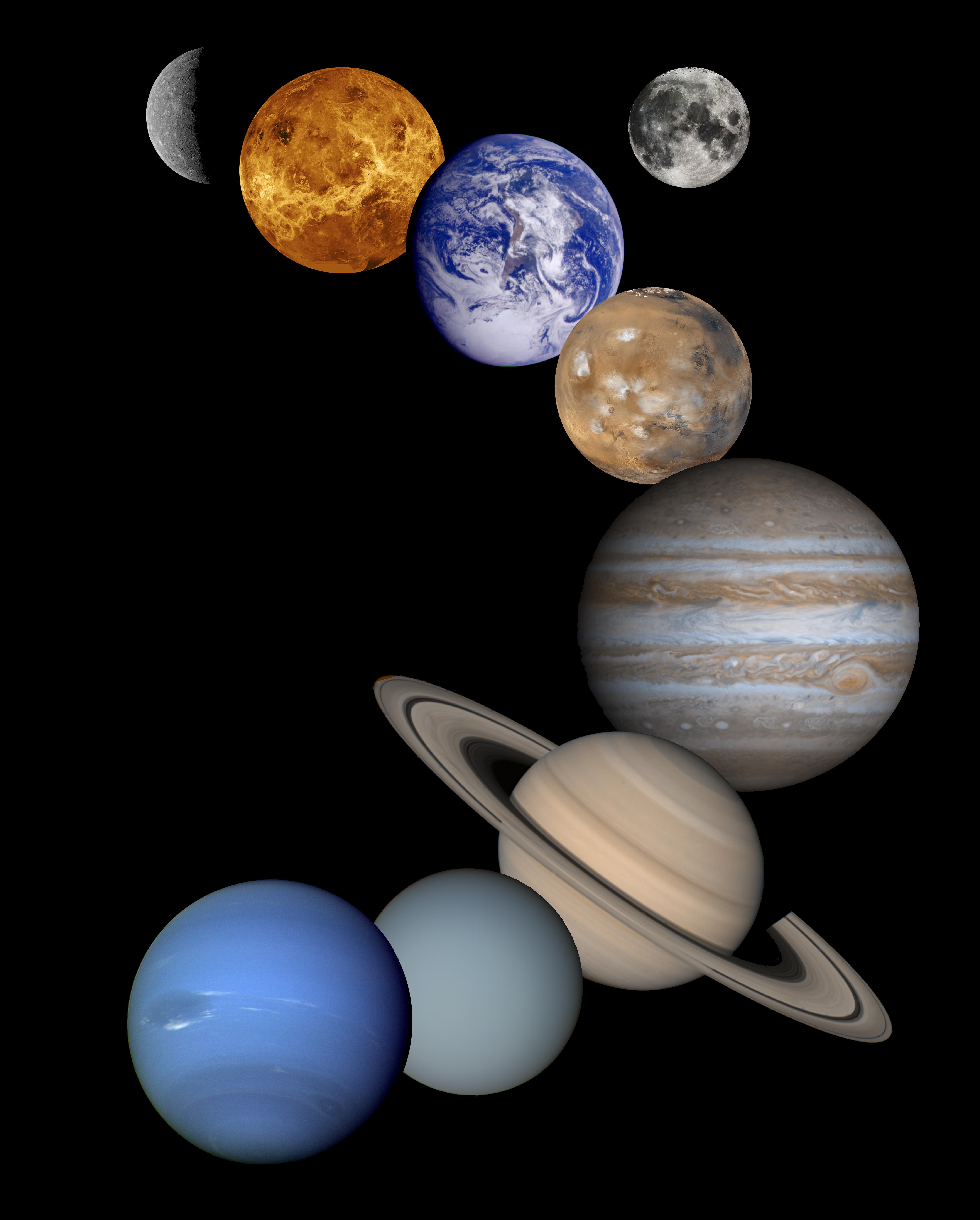

Gustav Holst’s “Planets”: A brief profile

In his best-known work, “The Planets”, Holst set the alleged astrological characteristics of seven celestial bodies in our solar system to music. The result is a planetary character study that also captures human traits in sound.

The realm of the inexpressible

Music of the Romantic period: A journey to the depths of the soul

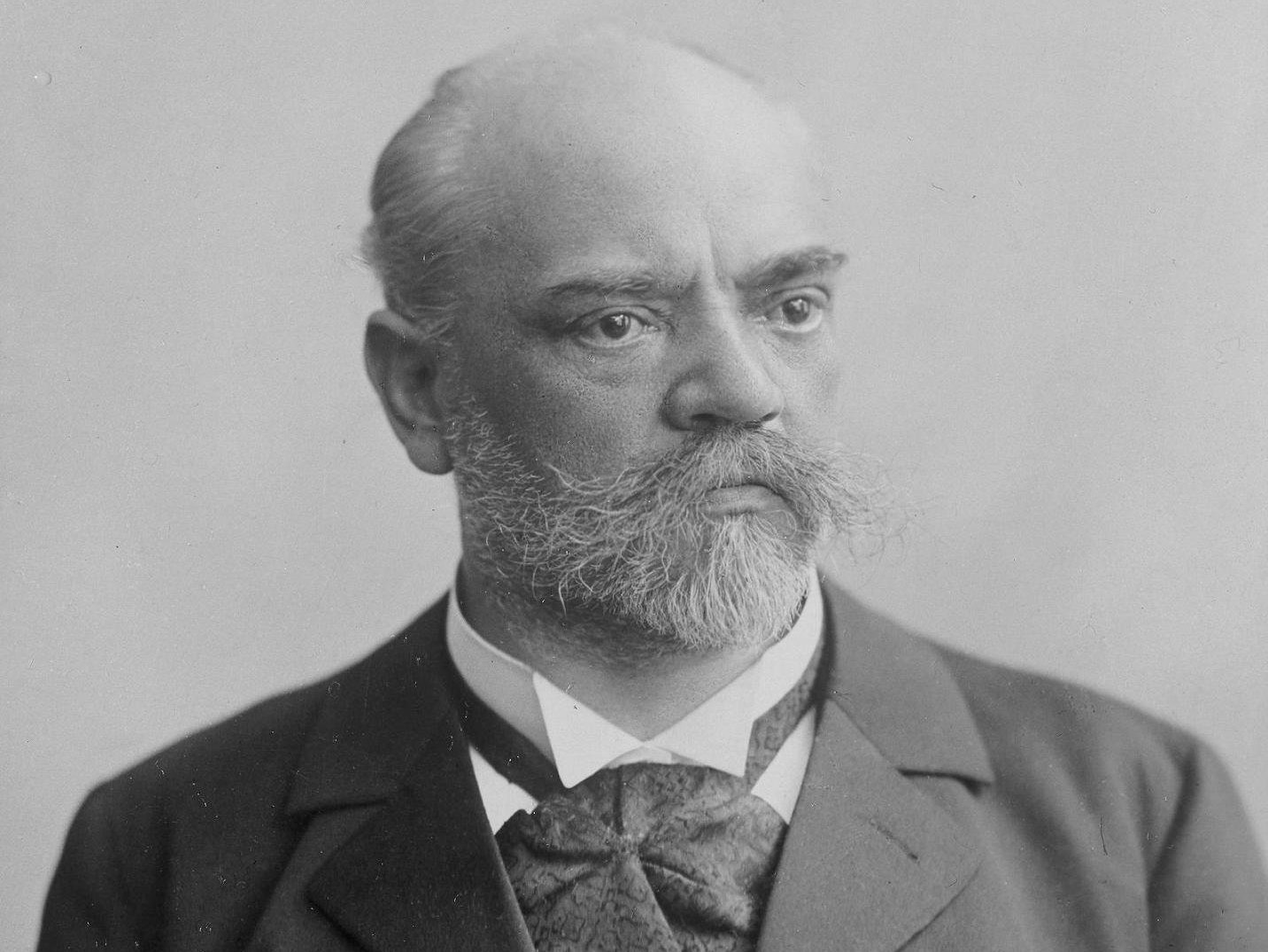

Dvořák’s path to fame

From orchestral musician to national composer – Antonín Dvořák had an unprecedented career. Thanks to his musical genius and his mentor.