Pianist, teacher and composer Ferruccio Busoni is a unique phenomenon in the history of music. His works are a fascinating blend of originality and depth, of intellect and heart, and of Italian Romanticism with German musical tradition – and yet he is at best a shadowy presence on today’s international concert programmes. The reasons for this are many and varied.

Italian by birth, Busoni chose to live in Berlin, where he arrived with his wife Gerda in 1894, at the age of twenty-eight. The couple lived on Kantstraße and Augsburger Straße before moving in 1910 to palatial accommodation at 11 Viktoria-Luise-Platz, in the district of Schöneberg. Their fifth-floor apartment not only housed a library of some 5,000 volumes; it also had its own lift. The Busonis arranged to have it specially installed; it led directly to a ground-floor tavern. The First World War brought an involuntary break to Busoni’s years in Berlin, his Italian ancestry forcing him as an enemy alien to flee for a time to Zurich in neutral Switzerland.

From the outset, Busoni’s life had been dominated by two different cultures: Italy and Germany. As the son of a German pianist and an Italian clarinettist, he was born in the Tuscan town of Empoli in 1866. Against such a background it was inevitable that his musical talents would be encouraged from an early age, and he was only seven when he made his debut as a pianist and as a composer, drawing widespread attention. The Austrian music critic Eduard Hanslick wrote enthusiastically of one of his early appearances: “Not for a very long time has a child prodigy struck such a sympathetic note in us as is the case with little Ferruccio Busoni, precisely because there is so little of the child prodigy about him. Instead, he has many of the qualities of a fine musician, both as a pianist and as a budding composer.”

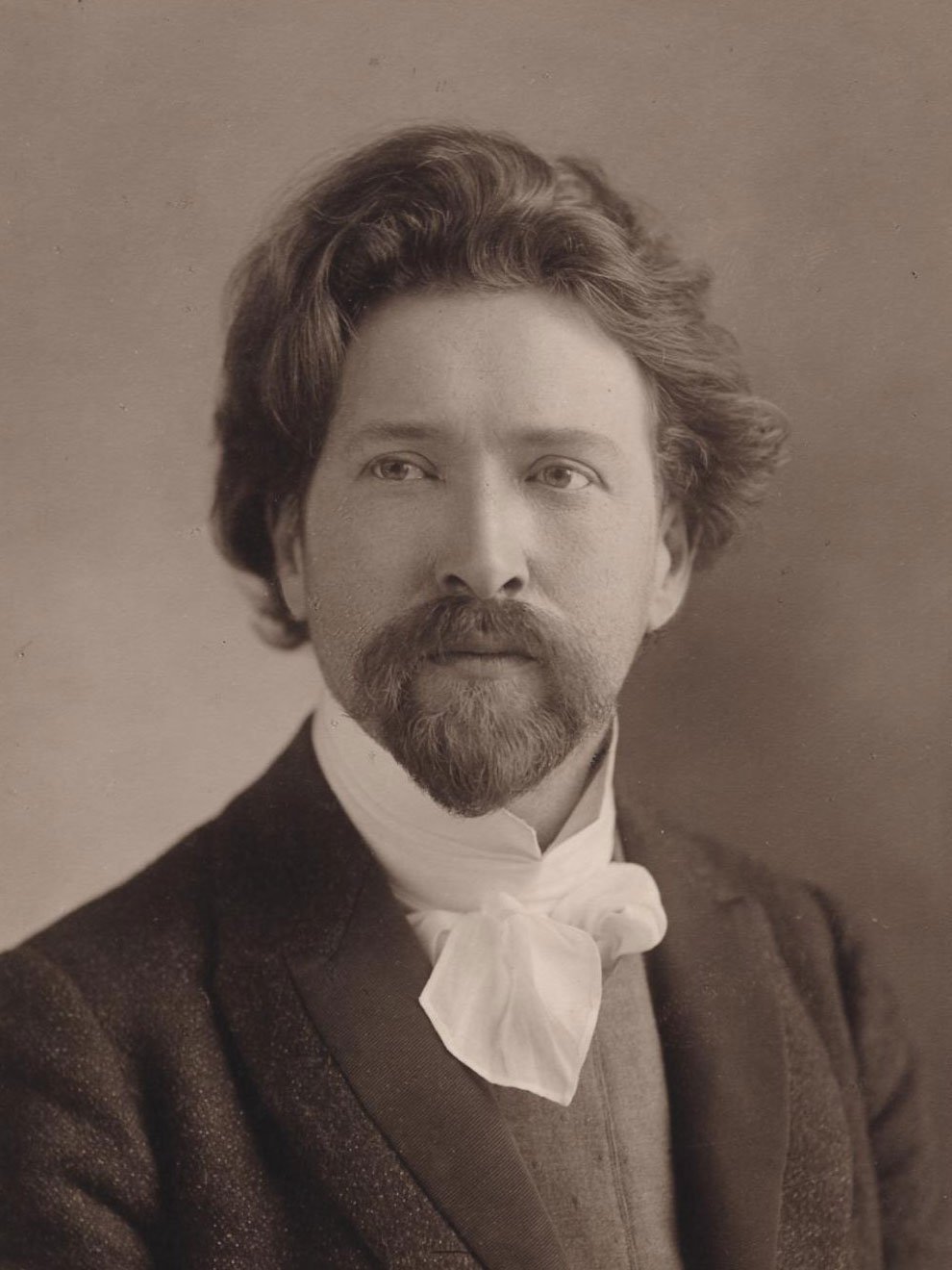

Busoni was a child prodigy

Between the ages of nine and eleven, Busoni studied at the Vienna Conservatory and by the time he was fifteen he had been accepted into the prestigious Accademia Filarmonica of Bologna – just over a century after the fourteen-year-old Mozart had been inducted into its ranks. At the age of twenty he received lessons from Carl Reinecke in Leipzig, where he got to know Delius, Mahler and Grieg. He also received encouragement from Brahms, who was to be one of the young Busoni’s most important artistic models. Thanks to this intensive apprenticeship Busoni was now ideally prepared for a career as a musician, with a network of contacts that extended across the whole of musical Europe.

The big wide world and its multiple opportunities proved a lure for the inquisitive young artist; he absorbed every influence like the proverbial sponge. On completing his studies, Busoni taught the piano at various conservatories. After a period in the Finnish capital, Helsinki, where he became a friend and advocate of Sibelius and met his later wife Gerda, he moved to Moscow, finally living in Boston between 1891 and 1894. In America he took a keen and intense interest in Native American music, an interest reflected in works like his Indian Fantasy for piano and orchestra of 1913/14.

By 1894 Busoni had elected to settle in Berlin, where between 1902 and 1909 he organized a series of concerts devoted to new and rarely performed music. Among the composers whose works were featured in these programmes were Elgar, Sibelius, Debussy, Nielsen, Delius and Pfitzner, all of them largely unknown at this time. Meanwhile, the masterclass in composition that he set up at the Academy of Arts in Berlin became a creative think tank, with pupils such as Kurt Weill and Ernst Krenek.

A man of “multiple characteristics, gifts and intellectual instincts”

But if Busoni toyed with musical modernism, that interest was largely theoretical. Admittedly he told his wife in 1908 that he was keen to “catch hold of a bit of the coming art of music and, where possible, sew a seam in it myself”. And the previous year, in his Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music, he had attempted to create a new balance between musical emotions and language, while in some of his other writings he had examined the possibility of dividing the whole tone into three parts rather than the traditional two, a proposal that had caused Pfitzner to mock him and warn of the “danger from the Futurists”.

Yet few, if any, of these considerations found their way into his own practices as a composer. In terms of his impact, he was never a radical innovator, but more of a commuter crossing international borders, playing inquisitively with the musical legacy of the past, notably that of Romanticism, and striving in a spirit of playful delight to take that legacy to its furthest extreme.

Busoni left an extensive list of works running to a total of almost five hundred, including four operas. He was also active as a writer, as an editor of the works of other composers, including Bach and Liszt, and as a scholar, teacher and conductor. According to his biographer Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, the many lives that he sought to combine within him turned him into one of those artists “whose whole nature resonates with the tension of manifold inner aspirations and with the incessant struggle that stemmed from the battles fought out by multiple characteristics, gifts and intellectual instincts”.

It may well have been this struggle between the different aspects of his creative personality that contributed to the fact that with the exception of a handful of his piano pieces his compositions continue to be largely overshadowed by his successful career as a keyboard virtuoso.

Facing life euphorically

But it is also possible that the shadowy existence that Busoni’s music continues to lead is due to the fact that many of his works are so hard to grasp. His broad educational background and the many ideas that are often reflected in his music did not exactly encourage others to accord that music the respect that it rightly deserves. This wealth of possibilities also risks becoming unduly complex, placing too great a burden on the listener. The dominant feature of his music is its challenging blend of originality and profundity, of head and heart.

In many respects what might be termed the spiritual dual nationality of these works also militates against their wider acceptance: the Romantic cantabile spirit of the music of a composer like Verdi has left its mark on Busoni’s style just as surely as the Baroque and Classical legacy of the various German-language schools of composition associated with names like Bach and Mozart. Busoni’s music is never shocking. It is never radically modern and it never alienates its audiences. Busoni sought, rather, to achieve a degree of balance between tension and its release, between bewilderment and beauty, and between inner turmoil and formal order.

With its male-voice chorus, a work like the Piano Concerto evinces a compositional abundance and a refusal to compromise that makes it clear just how uncompromisingly and how absolutely Busoni was committed both intellectually and emotionally to music and to its power to affect us. But he was no less addicted to wine and cigars, an addiction which, combined with a kidney disease, led to his premature death at the age of only fifty-eight.

He found his final resting place in the cemetery in the Friedenau district of Berlin, where he was in undeniably good company as it also contains the graves of the workers’ poet Paul Zech, the Romanian-born poet Oskar Pastior and Marlene Dietrich. Busoni’s grave is adorned and watched over by a statue by the sculptor Georg Kolbe depicting a figure with its arms outstretched, facing life euphorically.

A Wall-to-Wall Soundscape

A piano concerto of a special kind: Ferruccio Busoni created something completely new with his work for piano and male choir. The surprising choral entry in the finale lends the concerto an enchanting conclusion.

Ludwig van Beethoven the pianist

Ludwig van Beethoven was a piano prodigy; he enjoyed the greatest successes of his early career as a pianist. However, as his hearing deteriorated, this changed.

A short piano lexicon

Prélude, nocturne, sonata and étude – in our short piano lexicon, we introduce you to the major genres of piano music one at a time.