- Interview

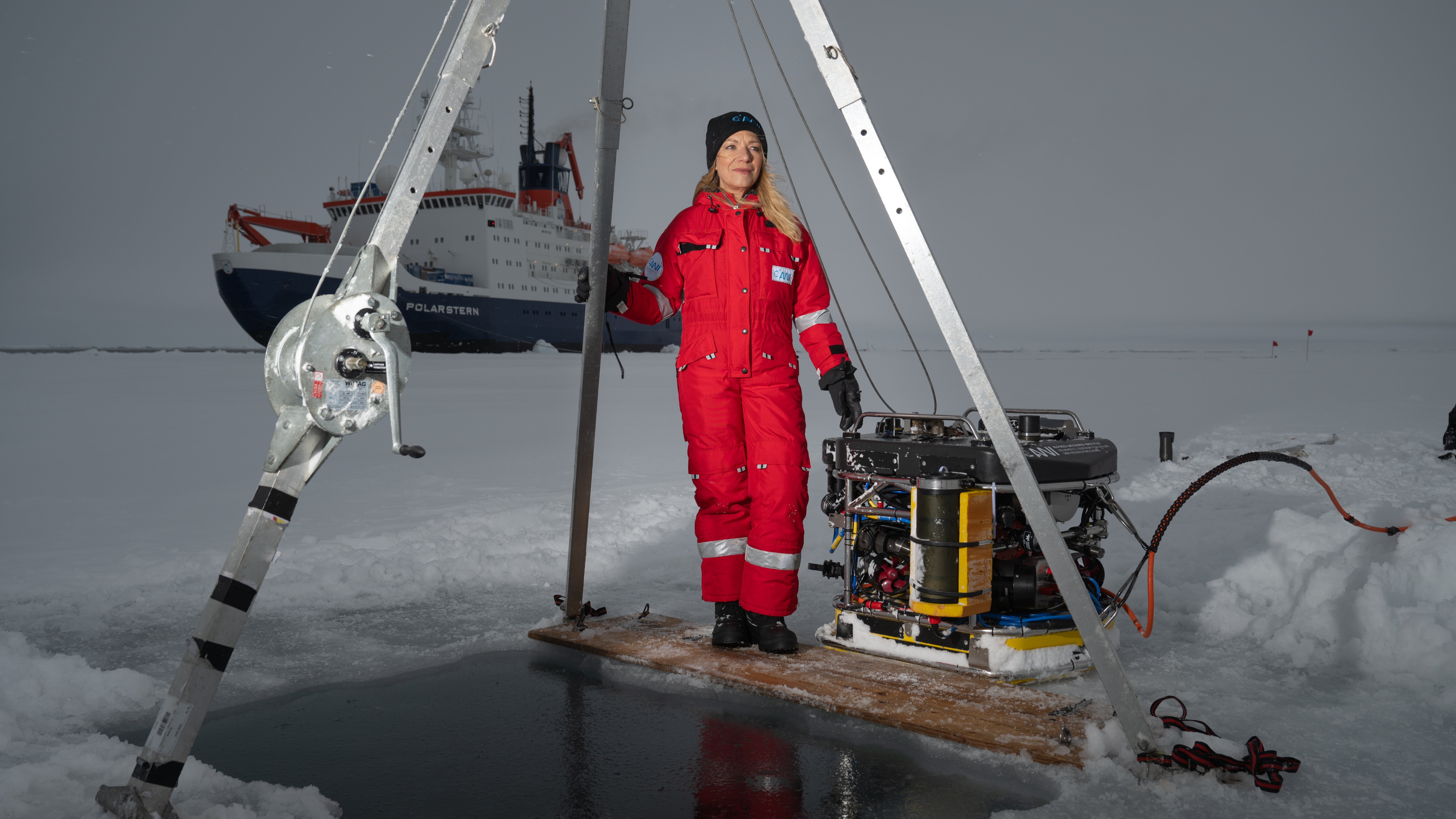

For the last seven years, Antje Boetius has been scientific director of the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven. In the spring of 2025, the German marine biologist will begin work as president of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in California. Before she leaves Bremerhaven, however, she will join a discussion at the Philharmonie as part of this year’s Biennale, Paradise Lost? In the course of our interview, she talks about what she is especially looking forward to, the role that climate change will continue to play in society, and whether we will ever truly learn to see the ocean as a gigantic habitat.

Frau Boetius, you will soon be moving to California to become the director of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), where you once studied oceanography. Which are you looking forward to seeing more: the country and its people? Or the Pacific?

It will be a total joy to see them all again. My capacity for joy is great enough for that. I also look forward to the scientific advances that MBARI can offer: running the Institute will give me a great opportunity to contribute even more to the development of innovative deep-sea technologies and to talk about the fascinating variety of life that exists in the ocean.

You have often spoken of the “world ocean” that connects the entire globe. Will you find a new area of research in California or only different perspectives on the same sea?

MBARI plays a leading international role in developing deep-sea technologies such as autonomous underwater robots and sensor technology as well as the most varied techniques for producing images and other ways of observing the ocean. Above all, I will have time to observe deep-sea life myself. One of the objectives of the Foundation funded by the Institute is the discovery of life forms alien to our own. We are also working hard to integrate Artificial Intelligence and Big Data in researching and protecting the ocean, which has given us completely new perspectives on both the Pacific and the ocean in general. I’d also like to work more closely with other scholars in the field of international polar research.

In February you will take part in an event at the Philharmonie in Berlin, when we will discuss the question of climate change and ask if this issue is disappearing from the political agenda. Will this question be more pressing than ever before during Donald Trump’s second term as United States president?

Protecting the climate and the environment is most definitely not disappearing from the political agenda, not even in America. It is becoming increasingly clear that protecting the climate is the most economical way of shaping the future and that this is a crucial question in matters of health, energy and economics. In the longer term no country can deny the need for change or avoid the increasing damage that would be caused if we were to continue down the present road.

Marine research is currently celebrating an anniversary that has largely gone unnoticed. A century and a half ago the HMS Challenger spent several years exploring the world’s oceans, a gigantic undertaking that is seen as the birth of oceanography as a science. Is this expedition still of significance today?

Absolutely! The HMS Challenger expedition lasted from 1872 to 1876 and it is still rightly regarded as a milestone in the history of oceanography. The same is true of the German response to it, the Valdivia expedition of 1898 and 1899. These global deep-sea expeditions laid the foundations for modern marine research. It soon became clear that, contrary to the assumptions of the time, the ocean depths were full of life.

HMS Challenger brought back thousands upon thousands of samples and a whole range of meter readings. Since then a vast amount of data has been collected using high-tech methods, including underwater robots. Indeed, there is so much data that it is almost impossible to analyse it all. The ocean is such a vast habitat that some might ask if we can ever really understand it.

It’s true, of course, that there are countless unanswered questions. These questions include the search for the origins of life in the ocean and the question of how exactly the earth’s tipping points can work with and without ice cover, together with the question of which of these tipping points will be reached as a result of the increasing build-up of CO2 in the atmosphere. Other unanswered questions include the tricks played by life in the ocean and the incredible lifespan of a number of these creatures as well as their ability to communicate, and questions concerning their immune system.

Anyone searching for aliens could just look to the world’s ocean depths. Research is yielding more and more insights into this extreme habitat, with its hitherto unknown creatures. Do you have a favourite among these discoveries?

I continue to be fascinated by the astonishing variety of life in the ocean, life that exists even at the greatest depths. And time and again new landscapes are being discovered on the ocean floor that no one knew about before. To take a single example: our team of researchers has discovered around sixty million nests of Antarctic icefish within an area of 92.7 square miles in the Weddell Sea. This represents an astonishing discovery that was possible only through the use of highly specialised technology that can operate beneath the ice. For my team and me. this was also a sign that we need to establish marine protection areas around the Antarctic as a matter of urgency. Equally exciting is our recent discovery of gigantic sponge mountains in the Arctic. These sponges can crawl along the ocean floor and live to be hundreds of years old. Fantastic!

It is often said that one way of preserving the oceans is to focus on the possible use of sea creatures not only for food but also for active substances that are of potential benefit to medicine. Is this the right approach?

The oceans are home to the greatest genetic resources in the universe. We can expect to observe many more important biotechnologies in marine organisms. They have tricks that allow them to live longer than other life forms. They can exist by using less energy and by living in a symbiotic relationship with other organisms. Even now, different kinds of value creation already include various bioactive substances that are important in treating a number of types of cancer or that can replace antibiotics and prevent cells from ageing. Enzymes from sea creatures are already being used in the food and energy industries. The genetic variety found in the high seas offers so many solutions! Research is still in its infancy. We still haven’t explored even one thousandth of this habitat.

You are in favour of improving our “survival skills”. These often include indigenous practices as part of a way of life that respects nature. Until relatively recently the ocean depths in particular were inaccessible to humans. Despite this, can we learn from traditional knowledge systems?

There are myths and narratives in many indigenous cultures that describe the ocean offering gifts to humans and helping us if we treat the ocean well and are not wasteful, but rather maintain a state of balance with it. In these stories, many sea creatures play a functional role in our lives, or may be sentient or even divine. In other words, many cultures accord a fundamental right to exist to the sea and to its life forms. They do not see the sea simply as a resource. Research also shows an immense scientific understanding on the part of early seafaring nations from the Inuit in the Arctic Ocean to the islands of Polynesia. Stars, ocean currents, winds and a knowledge of the migratory patterns of birds and whales – all of these things have played a role in navigation and in survival.

You are active as a researcher. In the future you will also be heading a major institute, while at the same time you are committed to spreading knowledge. What is the message that people – including politicians – should take away with them in terms of the importance of the world’s oceans?

That the ocean has to be a part of the solution if we are to lead peaceful lives in balance with nature and with the climate. Water covers 70% of the earth’s surface. It absorbs 93% of heat and redistributes this in such a way that our climate favours life. At present the ocean is still absorbing 25% of CO2 emissions and also producing much of the oxygen that we breathe. I am quietly confident that this knowledge of the ocean’s role in our lives is increasingly affecting the actions of politicians: there are many new ideas for protecting the seas and there is much more international cooperation. One basis for this cooperation would be for the cost of exploiting nature, the environment and our natural resources to be honestly calculated in a way that we can all understand. We should also reduce subsidies to companies that use processes that are harmful to the environment. We should acknowledge that we cannot manage without all that nature does for us, and we should protect this as a global resource, and develop new business models that make greater social participation possible.

Biennale: “Paradise Lost?”

In February 2025, the Berliner Philharmoniker’s Biennale will focus on the threat to nature. A festival with concerts, guests from the world of science and much more.

Nature and music

Composers of all ages have been inspired by nature to write magnificent works: only their aesthetic outlook and their individual approach have changed with the passage of time. Here is a brief survey of this subject

The Biennale 2025 exhibitions

Accompanying the Berliner Philharmoniker’s Biennale, entitled “Paradise lost? - On the threat to nature”, interesting exhibitions complement the programme.