- Portrait

Pianist Martha Argerich is often called the grande dame of the piano. Right from the start, she was heralded as an exceptional talent, and was said to be able to “play everything” at the age of twelve. But it’s lonely in the limelight, and Argerich prefers to share the stage with long-time associates like Daniel Barenboim. A portrait.

“Speaking is more difficult than playing,” Martha Argerich explained in one of her rare interviews. The pianist prefers to express what she has to say in music – with playing that has variously been described as spirited, vigorous, energetic, poetic, and sensitive. Her combination of ferocious intensity and technical brilliance have earned her titles like “tigress”, “tiger at the keyboard” or simply “Bella Martha”. Argerich herself has been described as headstrong, capricious, and unpredictable; she describes herself as “chaotic”. But she can also be shy, vulnerable, or reflective, as her daughter’s documentary film Bloody Daughter poignantly reveals.

From child prodigy to once-in-a-century musician

Argerich’s exceptional promise was already apparent in nursery school, when she is reported to have played melodies flawlessly on the piano at the age of three. Born in Buenos Aries to a mathematics professor and a mother who had Jewish ancestry from the Russian empire, Argerich was soon acclaimed as a child prodigy. She made her public debut at the age of seven as the soloist in Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto. In the mid-1950s, Juan Perón, then president of Argentina, granted Martha Argerich’s father diplomatic status to enable him to take up a post at the embassy in Vienna, so that his daughter could study with the equally brilliant and unconventional Austrian pianist Friedrich Gulda. He hardly knew what to teach the twelve-year-old, he later said, “because the girl could do everything”. Although she did not enjoy the early limelight and attention, Argerich managed to shed her child prodigy image and launch an international career.

With the Berliner Philharmoniker

When Martha Argerich made her debut with the Berliner Philharmoniker in March 1968, playing Bartók’s Third Piano Concerto, the then 27-year-old had not only won the prestigious International Chopin Piano Competition but had also gone through a serious life crisis. After the birth of her first daughter, she saw herself as little more than a piano-playing housewife, and withdrew completely from the stage in the early 1960s. It was only at the urging of her teacher Stefan Askenase that she returned to the limelight in 1964.

Her first appearance with the Berliner Philharmoniker was – according to the Tagesspiegel – “the kind of debut that you don’t experience every day”. She played the Bartók Concerto, wrote the critic, “in a breathtaking new way. Finally, someone comes along and shows how much chamber music there is in the score, exposes the magnificent dynamic shadings of the score and articulates its impressionistic wealth of colour.”

This performance was only the first of many celebrated collaborations. Argerich, who has an impressively broad repertoire, brought piano concertos by Tchaikovsky, Ravel, Chopin and Prokofiev to the Berliner Philharmoniker’s demonstratively enthusiastic public, along with several performances of Beethoven’s Second and the A minor Concerto by Robert Schumann, a composer with whom she claims a special affinity, not least because of the turbulence of his contrasting emotional worlds.

As a team player

Martha Argerich appeared with the Berliner Philharmoniker particularly often during Claudio Abbado’s tenure as chief conductor, travelling to Salzburg to perform with them several times, and appearing as a guest at the New Year’s concert in 1992. A particular highlight of that time: during Abbado’s Prometheus cycle, she played the highly virtuosic piano part in Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus: The Poem of Fire. A concert recording in the Digital Concert Hall conveys an impression of this explosive performance.

After the Abbado era, her appearances became less frequent; she was a guest of the Berliner Philharmoniker only twice, in 2007 and 2014. She returned to the orchestra in 2023, however – on this occasion, for the first time together with her childhood friend Daniel Barenboim. It was, according to German national weekly newspaper Die Zeit, a goosebump moment: when they step onto the podium, wrote the newspaper, “they fill the room – even before a single note is heard. With beauty, love, memory.“ From then on, she performed with Barenboim repeatedly.

Martha Argerich, an enthusiastic supporter of young artists, enjoys making music together with others. Orchestral concerts and, even more so, chamber music concerts are her passion, unlike solo recitals. She dislikes being alone on the stage, “naked”; the feeling of loneliness is too overwhelming, she says. She finds collaboration with others much more satisfying. “Music is a wonderful communication tool for me,” she says. And so she remains true to her nature: she would rather play than speak.

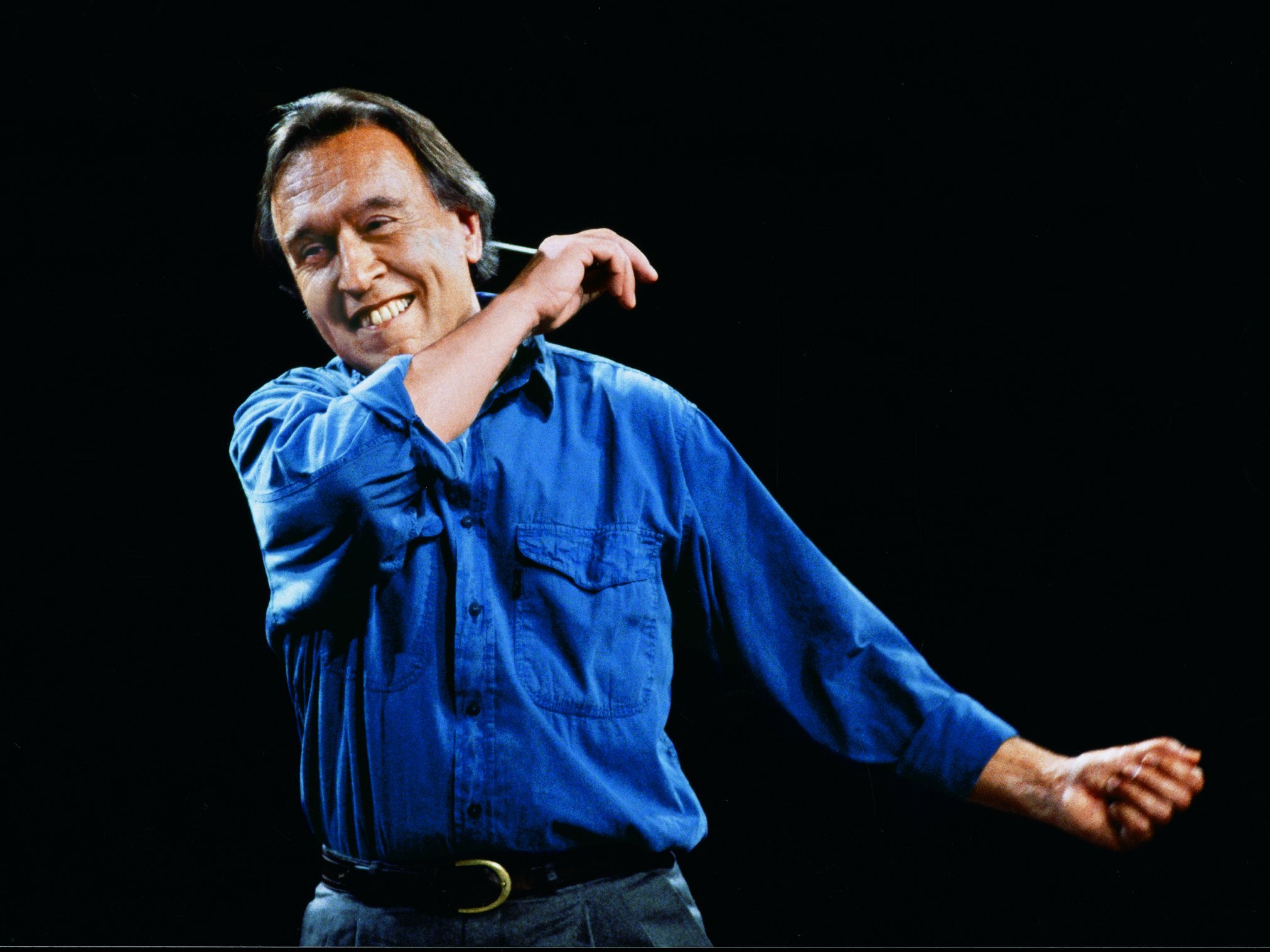

“I’m Claudio for everyone.”

With Claudio Abbado, chief conductor from 1990–2002, the orchestra experienced a turning point.

The Springtime of Love

For Robert Schumann, the early years of his marriage to Clara Wieck were a time of happiness and exuberant creativity. Some of his finest works date from this period.

A very special friendship

Daniel Barenboim conducting the Berliner Philharmoniker