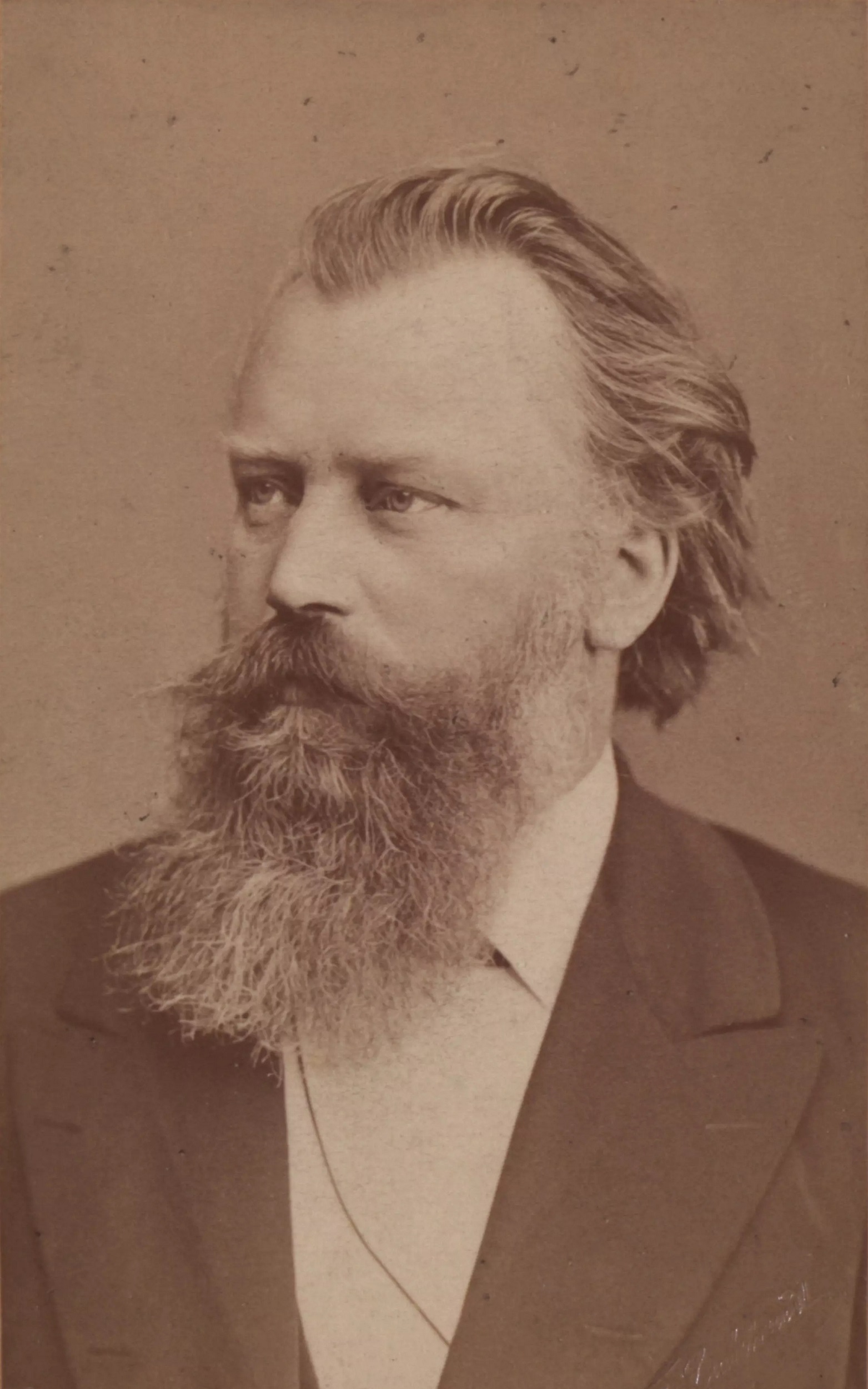

- Portrait

- History

Despite his relatively slender output, Paul Dukas was an influential figure on the French music scene at the beginning of the 20th century. On friendly terms with almost all the important composers of his day, he also maintained a healthy distance from the bitter controversies surrounding the works of Richard Wagner in his work as a music critic. His own music was firmly rooted in French Romanticism, but as Olivier Messiaen’s teacher, his influence extended far into Modernism.

Paul Dukas was a central figure of French musical life, although his catalogue of works comprises less than twenty titles. Of these, only the symphonic poem The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is played regularly, which – to put it inelegantly – makes Dukas a “one-hit wonder”.

The opera Ariane et Barbe-bleue, which was premiered in 1907 and, like Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, was based on a play by Maurice Maeterlinck, is regarded by experts as one of the most important French stage works of the early 20th century. These experts also included his contemporaries Zemlinsky, Schoenberg and Schoenberg’s pupils Alban Berg and Anton Webern, who sent Dukas an admiring congratulatory telegram on the occasion of the Vienna premiere.

In addition to the symphonic poem, the opera and three early concert overtures, Dukas composed a symphony, a ballet and a cycle of variations for piano; it seems as if the composer wanted to produce a single, exemplary work in all the important genres and that was enough for him. Conspicuous for French composers of his time is the unusual absence of chamber music – the Villanelle for horn and small ensemble is actually a concertante piece.

His extensive and time-consuming work as a music critic between 1892 and 1905 undoubtedly prevented Dukas from composing his own music; the publicly active composer outlasted the reviewer by only a few years, however. After the ballet La Péri, which had its premiere in 1912, Dukas published no more music until his death on 17 May 1935 and apparently destroyed most of the works he wrote during this period.

Bridge between Romanticism and Modernism

A more complete picture of Dukas’s pivotal position does not emerge until one also includes his work as a music critic and his relationships with the important composers of his day. For example, he maintained close friendships with Camille Saint-Saëns, Vincent D’Indy, Gabriel Fauré and Claude Debussy. Although some of these musicians thought little or nothing of each other, they all respected Dukas. Even the otherwise sarcastic Debussy had nothing but exceptionally favourable comments about him.

As a student of Georges Bizet’s close friend Ernest Guiraud and Olivier Messiaen’s teacher, Dukas, as is apparent from today’s perspective, was a link between French Romanticism and Modernism – a position that also characterizes his own works stylistically. And although he did not want to follow his friend Debussy into the realm of free, entirely autonomous forms, he nevertheless recognized Debussy’s genius early on.

The “case of Wagner”

Dukas was also crucial in his work as a music critic in that he kept to the middle ground amid the sometimes fierce controversies of his day. When Theo Hirsbrunner divides the composers of early Modernism into Wagnerians and anti-Wagnerians in the first chapter of his book on 20th-century French music, Dukas is assigned to the first group only during his early creative period. Later, D’Indy’s unreserved admiration for Wagner was just as alien to Dukas as Debussy’s opposing position.

As a music critic, Dukas strived for objectivity and impartiality. That also applied to the “case of Wagner”, which proved to be a fateful question for French music at the end of the 19th century. French Wagnerism had initially established itself as a literary movement, but during the formative early years of composers such as Debussy and Dukas it had long since spread to music.

At the same time, Wagner’s influence conflicted with the effort towards musical autonomy that French composers struggled with during this period. France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War also had a profound effect on the nation’s cultural self-awareness in 1871. In this context, attitudes towards Wagner ranged from the aim to outdo him in the operatic sphere by setting French mythological subject matter to music, to the demonstrative cultivation of genres not influenced by Wagner, and the music of the Group of Six around Darius Milhaud, which was supposed to sound as if Wagner had never existed.

As a critic well-versed in music history, Dukas did not identify with any of these options. On the one hand, he believed it was impossible to ignore Wagner’s indisputable achievements and innovations; on the other, he rejected the historico-philosophical implications of the New German School.

Wagner and his followers maintained that the history of absolute music came to an end with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and must be replaced with the music drama and instrumental programme music. Dukas’s compositions also demonstrate that he did not agree with this idea; they include both absolute and programme works, but not in the order of priority suggested by Wagner, since Dukas did not compose his Piano Sonata until after the symphonic poem The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.

“Melancholy of success”

Justice is a virtue, but not absolute, or in every case a productive artistic force. The example of Debussy, in particular, shows that the sometimes unjust or excessive criticism of the monumental figure of Wagner could also be profitable for one’s own positioning. Paul Dukas did not manage that, and in his late years he witnessed how musical schools disappeared anyway. And in a variation of the phrase the “melancholy of ineptitude” that Nietzsche aimed at Brahms, Giselher Schubert refers to the “melancholy of success” with Paul Dukas in mind. It characterizes a composer who, in the heterogeneous concert of Modernism, despite his technical expertise and rich knowledge of music history, perhaps could no longer find the entrance cue for his own voice.

Richard Wagner und Mathilde Wesendonck

The mysterious relationship between Richard Wagner and Mathilde Wesendonck

Between heaven and earth

Johannes Brahms and the Berliner Philharmoniker share a special history. We take a deeper look at his “Song of Destiny”.

9 Facts you (perhaps) didn't know about Verdi

You can hum along to “La donna è mobile” in your sleep, but did you know that Verdi was a vintner, a member of parliament and a keen foodie?