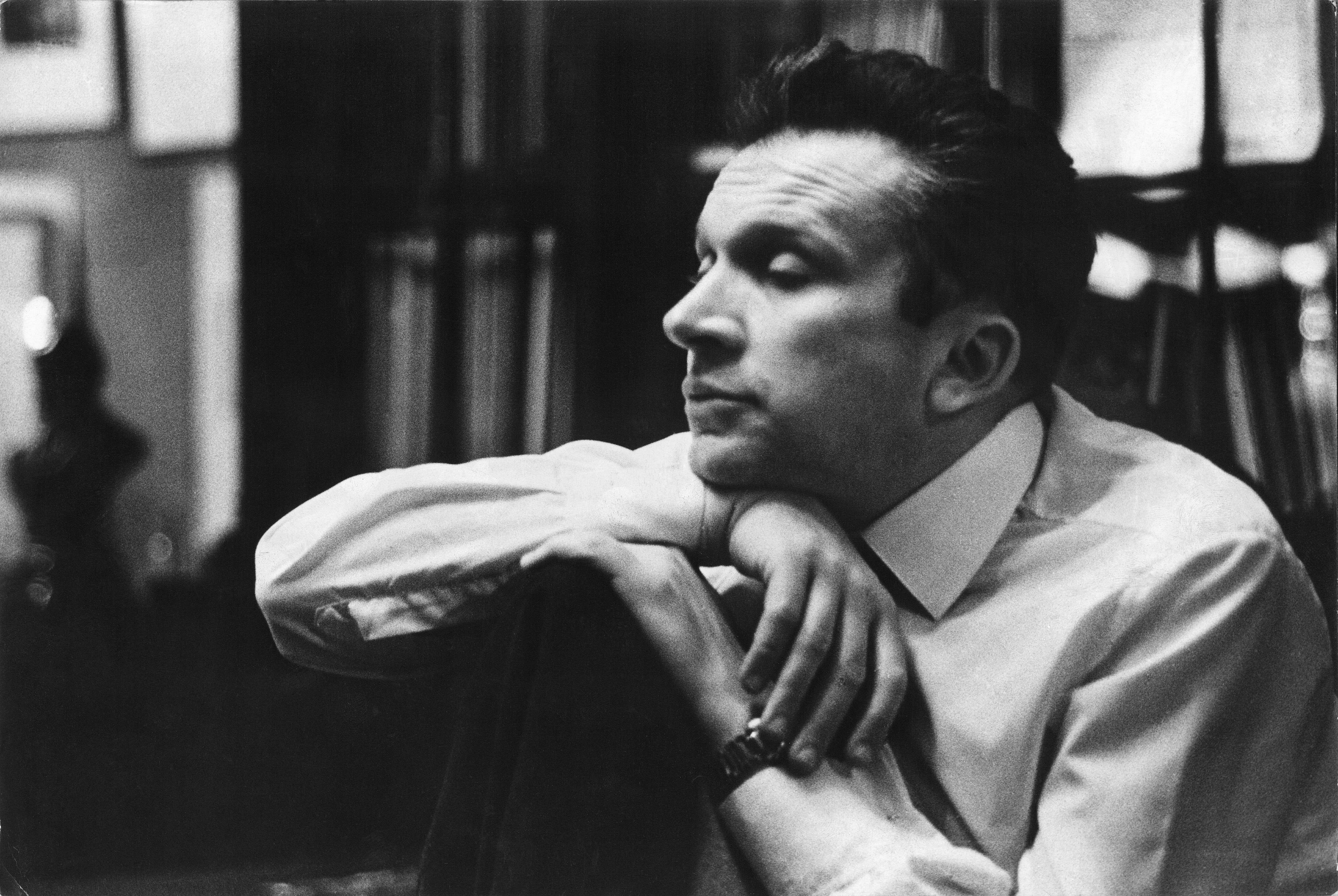

- Portrait

At first, Toshio Hosokawa found the traditional art of his homeland rather dull. Now, his roots are a source of inspiration for him. In March, the Berliner Philharmoniker will perform the world premiere of his concerto for violin and orchestra "Prayer". An encounter with a fascinating artist.

“I once met a leading Zen master who created a new kind of calligraphy every day. He said: ‘Calligraphy is not what results when you paint straight on to the paper. Instead, you fix on a point in space and then start to paint from this point before finally returning to it. This linear movement, radiating outwards in circles, is calligraphy.’ This idea has had a fundamental impact on my music.”

Calligraphy is a central point of reference in the thinking of Japanese composer Toshio Hosokawa, a point to which he has repeatedly drawn attention. He explicitly defines music as a “calligraphy of sounds that is painted on the canvas of silence”. Even more radical is his assertion that composition is an action designed “to deepen the intensity of silence, not the intensity of the sounds”.

Nature, tradition and the avant-garde

Nowadays Hosokawa’s ideas on sound are drawn essentially from three different sources: from the western avant-garde, to which he was introduced by his composition teachers in Berlin and Freiburg; from traditional Japanese aesthetics, including authentically Japanese instruments; and, finally, from the sounds of nature. Imitating nature is one of the basic principles of Japanese art, and Hosokawa, too, insists that “for me, the ideal music is a sound of nature”.

Toshio Hosokawa was born in Hiroshima in 1955 and his life initially ran in parallel with the modernization, westernization and industrialization of his native Japan. Japanese society’s belief in progress meant that traditional arts were increasingly forced into the background, a development that Hosokawa could witness at first hand: after all, his family was still powerfully influenced by traditional Japanese arts, including ikebana (the art of Japanese flower arrangement in which his grandfather was an acknowledged expert), the Japanese tea ceremony and traditional Japanese music.

But the young Hosokawa initially broke with tradition: “Back then, when I was still young, the traditional Japanese music that my grandfather and my mother had loved so much struck me as insipid and monotonous.

I was much more fascinated and impressed by western composers such as Beethoven, Mozart and Schubert, later also by the early modern movement in Europe as represented by Stravinsky, Bartók and Debussy. I sensed something excitingly modern in their works, something new and immensely powerful.”

It was only logical, therefore, that Hosokawa should study music in Europe, initially in Berlin, where he was taught by Isang Yun, later with Klaus Huber in Freiburg.

It was only here, in a foreign land, that he discovered his own musical roots. “They were organizing a festival in Berlin that was to showcase music from different nations and cultures and, at the same time, modern music. This was the first time that I had heard traditional Japanese music as ‘music’ and I was moved by its unique qualities and by the beauty of this world of sound.” Since this seminal experience Hosokawa has sought to write works that synthesize the advanced language of the western avant-garde with the sound world of ancient Japan.

Hosokawa: Concerto for violin and orchestra

The beauty of transience

Among the central and most fundamental experiences of Asian art is transience. Being is defined as becoming and departing, the present day as the intersection of presentiment and memory. “We Japanese”, says Hosokawa, “regard the fleeting quality of the transient as a thing of beauty, which is why we love sakura, cherry blossom in spring. It blossoms only briefly – four or five days at the most, after which the blossoms fall to the ground. We regard this process of the falling blossom as a thing of beauty. Our lives, too, do not last for ever. They blossom briefly and then they fade away and thanks to this awareness of transience we feel that those lives are precious.”

This view of the world is a key point of reference in Toshio Hosokawa’s work: “We hear the individual notes and at the same time perceive and evaluate the process by which these notes are born and disappear – they resemble what I might call a landscape of becoming that is animated by musical sounds.” A corresponding degree of attention is invested in the individual note or sound: “My compositional method is invariably based on the act of perceiving a specific sound in all its depth, immersing myself in that sound and listening to its inner sound world.”

Calm, nature and solitude: this is my Japan

Toshio Hosokawa has contributed to practically every genre and has received numerous honours and awards for his works. He has lived for the most part in the great capitals of Japan and Europe but is essentially someone who feels particularly close to nature.

His great sensitivity for tranquillity, for quiet and slow developments is motivated by his search for what lies at the wellspring of our lives and his identification with an alternative Japan: “Japan is multifaceted. On the one hand there is pure stress in the big cities, while on the other hand there is still a sense of calm outside the main centres, where nature and a feeling of solitude still exist. That’s my Japan, those are my roots.”

In many respects Hosokawa’s ideas on music overlap with the ideal associated with shakuhachi music, which is mainly about depicting the sound of the wind blowing through a bamboo grove as a symbol of our bond with nature. It makes sense, therefore, that he regards composition as “a way of behaving that is always in harmony with nature”.

And yet Hosokawa is always painfully aware of the extent to which nature is under threat in today’s world. In 2016, for example, he wrote an opera, Stilles Meer (Silent Sea), that examines the natural disaster of Fukushima: “I myself was in Fukushima. I saw the towns in which no one lives any longer. It was terrible. It looked like our future, like the end of the world. I was born in Hiroshima. Before I was born, this city suffered a major disaster. And then came Fukushima … This was a great shock for me and since then I have spent a lot of time examining this topic. There’s a scene in the opera in which people go to the sea with lanterns and give their lights back to the sea. This ritual expresses our belief that the human soul comes from the sea and returns there when we die. But the sea is no longer clean. So where can we go when we die?”

Music sketched with an ink drawing brush

Toshio Hosokawa has successfully achieved a balance between an advanced western musical language and his own musical roots, roots that are grounded in a completely different culture. “The blossom of the lotus”, he writes, “symbolizes the opening up of the mind, the awakening of the self and our profound longing for illumination and beauty. The flower and I are one – the song of the flower is my song. And the blooming of the flower represents the moment when I lose my leaves and discover myself.” This moment of self-discovery has nothing to do with any subjective, solipsistic navel-gazing.

For Toshio Hosokawa, writing music has nothing to do with describing his own expressive and emotional worlds. His lotus flower has nothing in common with the blue flower of the German Romantics. But his musical language is so vivid and so universal that despite its close links to the aesthetics of Asia it is understood all over the world. These are sounds that breathe, sounds that seem to be sketched with an ink drawing brush: delicate but highly concentrated and bursting with energy.

Klaus Mäkelä, the Man Who Knows No Fear

In April, the Finn Klaus Mäkelä makes his debut with the Berliner Philharmoniker with works by Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich.

“It’s never enough, it can never be too much”

The conductor and harpsichordist Emmanuelle Haïm is one of the leading protagonists of early music. Portrait of a baroque icon.

And the Pain Remains Forever

The composer Mieczysław Weinberg is one of the great unknowns of the 20th century. A portrait