- History

Maeterlinck’s play Pelléas et Mélisande is a major symbolist work. Symbolism juxtaposed the brutally harsh reality of the late 19th century with a fascinating alternative world. It was full of poetic beauty, mystical allusions and sensory dreams.

A spring in the forest, an ancient castle, the “well of the blind men”, a seaside grotto, a musty vaulted cellar – those are the scenes in Maurice Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande. The drama transports the audience to a dark, mysterious, fairy-tale world: Prince Golaud meets a beautiful, enigmatic woman in the forest, takes her to his castle and marries her. But Mélisande feels like a stranger there, and comes to trust only Golaud’s half-brother Pelléas. That arouses her husband’s jealousy. He kills Pelléas; Mélisande dies of grief. Although Maeterlinck’s characters live at a time that is vaguely distant, their emotional lives are modern, and their nerves as chronically overwrought as those of city-dwellers in the late 19th century.

Prince Pelléas is depicted as a sensitive young man. Although his half-brother Golaud assumes the role of the power-conscious heir to the throne, he is nevertheless able to hear nuances, to sense atmospheric tension. And with the figure of Mélisande, Maurice Maeterlinck created a prototype of the femme fragile, the “frail woman”: delicate, pale, unaware of her own beauty and thus alluring, melancholy, fascinatingly otherworldly.

“Pelléas et Mélisande”: A theatre hit

Pelléas et Mélisande became the greatest hit of turn-of-the-century European theatre. On the one hand, audiences could recognise themselves in the protagonists; on the other, they were drawn into a fascinating dream sphere, where the characters move like silhouettes, where words and deeds have multiple meanings, and places double as metaphors.

Maurice Maeterlinck was one of the most important exponents of Symbolism, which originated as a reaction to the predominant literature of realism and naturalism. “Each new evolutionary phase of art corresponds precisely to the senile decrepitude, the inevitable end of the school immediately preceding it,” the poet Jean Moréas wrote in 1886. Romanticism was outdated, he declared; naturalism, however, was an “ill-advised protest against the blandness of certain novelists then in fashion”. Moréas called for change: “The cliché, that is to say the commonplace, when it becomes a chronic state, in poetry, as in everything else, is death. To live is to breathe the air of the heavens and not the breath of our neighbour, even if that neighbour were a god!”

Symbolism: The bubble of the art world at the turn of the century

Literary critics called the new movement decadent, but Moréas proposed the term “Symbolism”. The works of Stephane Mallarmé and Arthur Rimbaud served as sources of inspiration; Alfred de Vigny and even Shakespeare were praised as ideals. According to Moréas, the goal was to sensitize readers to the mysterious and unspeakable, with unpolluted terms, a new vocabulary full of “significant pleonasms, of mysterious ellipses, the anacoluthon in suspense; all daring and multiform”. In a novel the figures move through their own hallucinations; in poetry it is necessary to throw off the constricting shackles of classical rhyme schemes.

And then there is also synaesthesia, the simultaneity of different sensory perceptions: sound, colour and smell are to be incorporated into literature in order to penetrate into previously unknown spheres of beauty and eroticism, into the boundaries of consciousness. That is how l’art pour l’art, art for art’s sake, ivory-tower art emerged. Symbolism was the bubble of the art world at the turn of the century.

Artistic reactions to the rapid industrial expansion in the late 19th century

The public gladly accepted this invitation to escape from reality, because the reality around 1900 frightened many people. The social upheavals due to industrialization, secularization and scientific innovation were too great. Cities grew into megalopolises at breathtaking speed; the pace of life became faster and faster with steamships, trains, busses and the first automobiles. This radical turning point was reflected in the term fin de siècle, the end of the century.

But artists rebelled against the absolute faith in progress of the newly rich middle class and the profiteers of capitalist exploitation. Symbolism was only one of the artistic reactions to economic growth; the transitions to Impressionism, Art Nouveau and Surrealism were fluid.

In the realm of painting, Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon and Puvis de Chavannes are important exponents in France, Arnold Böcklin and Ferdinand Hodler in Switzerland, Fernand Khnopff in Belgium, Edvard Munch in Norway and Max Klinger in Germany. Legends and fairy tales fascinated them, everything dark, otherworldly, stylized, as well as evil, passion and the connection between eroticism and death. The Austrian artist Gustav Klimt became the greatest star painter of his time, with his unparalleled ability to weave his models into a cocoon of sumptuousness.

The most opulent decoration in every conceivable stylistic direction

Ornamentation became one of the most important design principles of art during the late 19th century: the most opulent decoration in every conceivable stylistic direction, luxurious ornaments and imaginative embellishments conceal the forms, even cover them at times, whether in literature, painting, music or architecture. Although many impressive buildings were constructed as steel frame structures, this innovative technology was concealed by ornamented historical facades.

The Eiffel Tower in Paris sparked off heated debate at the 1889 World’s Fair, because it dispensed entirely with such ornate and artificial covering and thus looked bare to many observers. At the next Exposition in the French capital in 1900, the supporting structure of the exhibition halls actually disappeared behind plaster and stucco.

The late Romantic composers followed a similar principle: they unleashed incredible sensory excitement with huge orchestral forces, extreme polyphonic complexity and ecstatic tonal splendour – as musical decoration.

They did not break through the traditional structures of functional tonality, however. They continued to respect the rules of the major-minor system, according to which every harmonic development, no matter how daring, must ultimately resolve to the home key. Although Gustav Mahler, Franz Schreker and Claude Debussy came very close to the boundaries of the system in their works, Arnold Schoenberg was the first to dare to take the final step and radically shatter tonality, after composing masterworks of musical Symbolism with scores such as Pelleas und Melisande.

Das Fin de siècle

Art of decay and new beginnings, decadence and closeness to nature

Unconditionality

Our programme on the sesquicentenary of Schoenberg’s birth

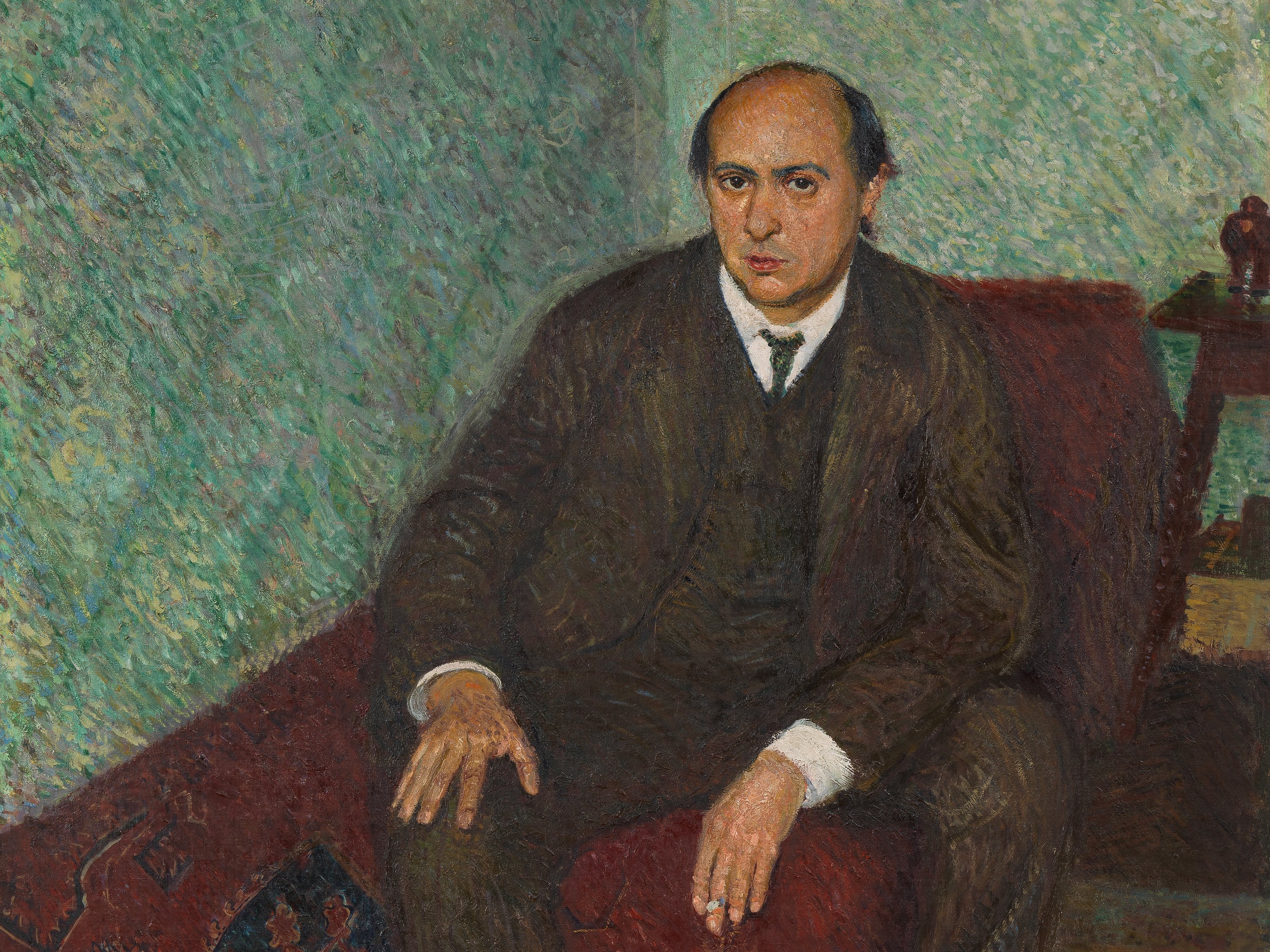

Schoenberg revealed

Three unknown sides of the composer Arnold Schönberg