- Philharmonic Moments

Richard Strauss owed practically everything to Hans von Bülow. Their mutual admiration seemed boundless, until a performance of Don Juan in Berlin cast a permanent pall over their relationship. A Philharmonic moment.

No other great composer was as successful in the concert hall from as early an age as Richard Strauss, and none was praised as fulsomely. The already-legendary conductor Hans von Bülow was alerted to the existence of the Serenade for Thirteen Winds by the young Munich composer. He found a publisher for the work and performed it with his Meiningen forces in 1883, after which he commissioned a second piece for similar resources. And he invited Strauss to take his baton at a concert in Munich.

This gesture was an unexpected sign of favour on Bülow’s part, the Bavarian capital having particularly hurtful and hateful memories for him: it was here that twenty years earlier he had encountered violent opposition as the conductor of Wagner’s operas. Amongst his enemies from that time, there was one in particular whom he could not forget : a horn-player by the name of Franz Strauss. Many years later Franz’s son, Richard, recalled the embarrassing reunion between the two old adversaries at the time of his first concert in the city.

“Bülow did not even listen to my debut; smoking one cigarette after another, he paced furiously up and down the Green Room. When I went in, my father, profoundly moved, came in through the opposite door in order to thank Bülow. That was what Bülow had been waiting for: like a furious lion, he pounced upon my father: ‘You have nothing to thank me for’, he shouted, ‘I have not forgotten what you did to me in this damned city of Munich. What I did today I did because your son has talent, and not for you.’”

Anger at the father, admiration for the son

Talent? This was undoubtedly an understatement. Bülow told the twenty-year-old Strauss that he numbered him among musicians with “exceptional” abilities whom he thought cut out “for an immediate appointment among the highest echelons of conductors”. Writing to the Berlin concert agent Hermann Wolff, he described Strauss as “an uncommonly gifted young man, […] only Brahms has more personality than he does … versatile, eager to learn, tactful but with a firm beat, in short, a first-rate resource.”

Bülow’s high regard for his younger colleague found expression in his concert programmes in Meiningen, where he ensured that Strauss was appointed – first as his assistant, and later as associate conductor of the nationally-acclaimed Court Orchestra.

Bülow had trained it with military precision and turned it into the country’s leading Beethoven orchestra, taking the players on numerous tours and demonstrating how to do justice to the titanic a composer - through pathos and precision. Shortly afterwards, he assumed the role of music director of both the Hamburger and the Berliner Philharmoniker, totally subjugating his audiences with his characteristic grandezza.

Catapulted to fame

Strauss succeeded Bülow as principal conductor in Meiningen, but he was catapulted to fame at sensational speed, and after only a year, he moved on to the Munich Court Opera.. His works were performed throughout Germany and even as far afield as the United States; the New York Philharmonic gave the world premiere of his Second Symphony in F minor in 1884. Strauss was good at forging new contacts, some of which were to prove useful in the longer term, most notably his acquaintanceship with Ernst von Schuch, who, starting in 1901, was to conduct the first performances of Feuersnot, Salome, Elektra and Der Rosenkavalier in Dresden.

Hermann Levi conducted the premiere of Strauss’s First Symphony in D minor in Munich, while Franz Wüllner – the principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic until replaced by Bülow in 1887 – was one of his earliest and most persistent champions. In addition to conducting the German premiere of the Second Symphony in F minor in Cologne, he directed the world premieres of Till Eulenspiegel and Don Quixote with the Gürzenich Orchestra. Bülow programmed the Second Symphony in Hamburg, while he also introduced Berlin audiences to Don Juan and the Burleske for piano and orchestra, and invited Strauss himself to conduct Aus Italien and Tod und Verklärung in the capital.

The conflicts could initially be hidden, but Bülow’s performance of Don Juan in Berlin on 31 January 1890 caused a perceptible rift and led to feelings of ill will. The critics targeted the work, while defending the conductor: “So much immoderation in terms of expression and such lack of clarity with regard to the presentation,” complained the Vossische Zeitung.

“What a brutal musical language, what exaggerated emotions - thanks not least to the strident high trumpets and horns, the ungainly tuba, the violently intrusive cymbal clashes, the crass dissonances in the harmonies! Following the performance, which constituted a masterful achievement on the part of the orchestra and its conductor, Herr von Bülow demonstratively applauded the composer, who was present in the hall, indicating what the audience should think about the piece. Herr von Bülow loves to create an atmosphere in this way.”

Don Juan as a divisive force

Strauss himself hated this whole approach. He was already disappointed at not having been asked to conduct his new work in Berlin, and in a letter to his parents, he complained that Bülow had not been in the least bit interested in the piece and in its poetical content. He had adopted the wrong tempi, creating the impression of a work notable only for its sophisticated instrumentation. Four days later, Strauss conducted the work himself, again with the Berliner Philharmoniker, but this time at a tempo that was around a third faster. In this way it may have been possible to rescue Don Juan, but not his relationship with Bülow, who proceeded to distance himself from Strauss; he was beginning to find his protégé’s development as a composer more and more perplexing.

Bülow tried to delay the local premiere of Tod und Verklärung, and maintained a stony silence when Strauss successfully performed the piece in February 1891. Years earlier, Bülow had prevailed on Strauss to revise the score of Macbeth, Strauss’s first symphonic poem, describing the initial version as “witches’ cauldron bubblings,” before conceding that the third version of 1892 was “mad and benumbing for the most part but in summo grado, a work of genius”.

For his part, Strauss criticized Bülow’s reactionary taste, but never questioned his phenomenal abilities as a pianist and conductor. On the other hand, he boycotted Bülow’s funeral. Bülow had died in Egypt in 1894, having travelled there in a desperate but futile bid to find relief from his incurable illnesses. It would have made sense to entrust the memorial concerts to Bülow’s favourite pupil and to perform some music by Brahms, but Strauss insisted on conducting only works by Wagner and Liszt.

The memorial concert in Hamburg was conducted by Gustav Mahler, the one in Berlin by Ernst von Schuch. Within a year, however, Strauss’s ideological rage had cooled, and during the 1894/95 season he worked as Bülow’s successor in Berlin, programming the latter’s Byronic fantasy Nirwana and even conducting two pieces by Brahms. By 1909, in his Personal Reminiscences of Hans von Bülow, it was no longer hard for him to praise his great patron to the skies – Strauss was by now well on the road to becoming a reactionary himself.

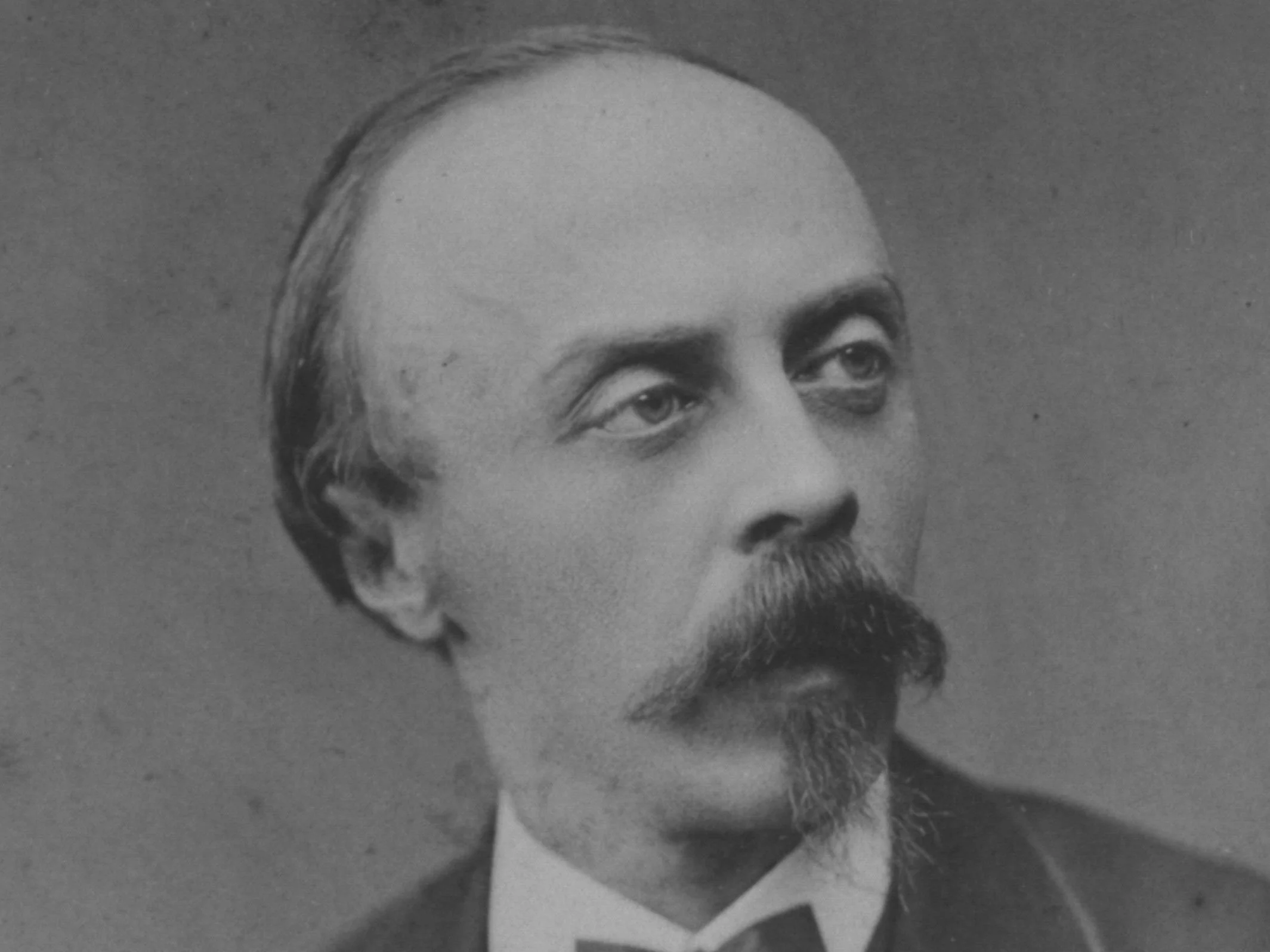

Hans von Bülow

Hans von Bülow, chief conductor 1887–1892, pulled the Berliner Philharmoniker out of their "well-behaved mediocrity".

Richard Strauss’s “Metamorphosen”: An introduction

The title derives from the ancient Greek and implies music that transmutes and transmogrifies incessantly.

Richard Strauss and the Berliner Philharmoniker

On the first visit, the orchestra did not leave a good impression with Richard Strauss – they were to change that completely.