- History

The idyll embodies the longing for a simple, peaceful life far removed from the tensions of modernity. In music and art it symbolizes a better world, idealistic and yet fragile. Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony is a striking example of this.

No wide roads dissected the countryside, no conveyor belts or assembly lines left workers feeling alienated, and there were no skyscrapers disfiguring the skyline when Beethoven wrote his “Pastoral” Symphony as a tribute to country life. Like the composer himself, many townsfolk enjoyed spending time in the villages dotted between woods and fields, where Beethoven sought out the idyll that he rarely found in Vienna’s urban environment. What he discovered in the countryside was the harmonious coexistence of man and nature.

Even in 1800 there were already signs of the tremendous upheaval that industrialization would bring in its wake. Steam engines were already in use in the textile industry, steam-driven locomotives were used for transporting goods from mines and within only a few decades railway lines were connecting half of Europe. The contrast between town and countryside and between industrialized civilization and the unspoilt world of nature was becoming ever more apparent.

A “little picture” of rural life

The arts seized on this contrast and used the idyll to conjure up a picture of a better world. The word “idyll” comes from Ancient Greek and derives from “eidyllion” (εἰδύλλιον), the diminutive of “eidos” (εἶδος), meaning “form, shape, picture or idea”. So an idyll is a “little picture”. It was the Greek poet Theocritus who created the genre of the idyll, a short poem, often in the form of a dialogue between shepherds, that depicted rural life in an ideal state of untroubled innocence.

Two centuries later Virgil revived the genre with his bucolic poems and these in turn were taken up by Renaissance poets. In the visual arts, too, there was a grateful audience for these artists’ idealized depictions of pastoral scenes set in an idealized world of nature.

Remembering a past that never existed

These works all evoke a picture of a Golden Age. By now the idyll was seen as the very embodiment of a simple, peaceful life in the country. It recalls a past that never existed and as such it cries out to be set to music, the art that fades as soon as it has sounded. Ever since poetry and music have existed, there have been pastoral scenes – the adjective “pastoral” derives from the Latin word for a “shepherd”, pastor. The early music theatre also took up this theme.

But pure happiness is unsuited to tragedy and can never be more than its starting point. In Monteverdi’s opera L’Orfeo, for example, the idyll serves a dramatic purpose as a state of happiness that is destroyed by a sudden event. From that moment onwards the individual embarks on a struggle to restore the initial state.

A fragile alternative to the bottomless pit of human existence

As Classicism gave way to Romanticism and the limits of reason became ever more apparent at the end of the Age of Enlightenment, the idyll emerged as an alternative to a present that was perceived as something terrifying. Mankind realized that whatever reason could achieve, it was unable to explain everything that takes place in the human psyche. Music ceased to be a reflection of all that could be seen and heard and instead sought to reproduce whatever these events trigger in human beings. Beethoven was one of the first composers to listen closely to the observer’s emotions. The following generation delved even more deeply and the Romantics revealed all that was eerie and sinister as an element of human nature, but this meant that the idyll became all the more important as a fragile alternative to the bottomless pit of human existence.

Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique postdates Beethoven’s Sixth by little more than two decades and in that sense it is the “Pastoral” Symphony’s successor. It may be said that in composing this work Berlioz brought the theatre to the concert platform. As the German musicologist Wolfgang Dömling has observed, “Beethoven’s first movement describes what its heading calls ‘The awakening of cheerful feelings on arriving in the countryside’, while Berlioz speaks of a vague des passions – a ‘wave of passions’. What both composers have in common, therefore, is the depiction of universal emotional states of the symphony’s ‘poetic subject’. In each of these works the following four movements are in contrast to the first one. They represent scenes of a kind that might be observed in the outside world and as such resemble stage tableaux.” Berlioz depicts his two shepherds playing a ranz des vaches – a type of song with which Alpine herdsmen summoned their cows and took them back to be milked – and imagines them performing the melody on a shawm on two mountain peaks in the Alps. On the one hand these herdsmen are closer to Heaven, while on the other they quite literally risk plunging into the abyss. As Dömling explains, “The scenes that unfold in the Symphonie fantastique do so in a world of dreams and of the imagination”, in that way revealing the immense distance that has opened up between them and the untroubled genre paintings that constitute Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony. With Berlioz the mountain idyll soon turns into an opium high and a Walpurgisnacht nightmare.

Too beautiful to be true

British composers found another meaning in the transfiguration of nature and sought their salvation in the countryside, where they hoped to develop their own musical identity away from mainland Europe and unbothered either by colonial problems or by the Moloch of metropolitan life. Pastorale Träume (Pastoral Dreams) is the title of a study by the German theologian and musicologist Erik Dremel that is very much worth reading and that describes the way in which nature has been idealized in English music. All too often, however, this music sounds “a little too much like a cow looking over a gate”, as the composer Peter Warlock maliciously observed.

Gustav Mahler’s idylls, on the other hand, have something otherworldly about them: they inhabit the world of the imagination, too beautiful to be true. In the middle of the development section in the opening movement of his Seventh Symphony, for example, there is a passage that seems like a vision of other worlds, an island to which we are spirited away from our everyday concerns and that Mahler himself described as opening up a “vista on a better world”.

Harbinger of disaster

Similar islands of idyllicism may be found in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century operas, except that here they mirror the main action in a condensed and cryptic way. Wagner’s Tannhäuser and Puccini’s Tosca contain arguably the two most famous pastoral scenes of this kind. In both of them young shepherds with androgynous voices – either a soprano or a boy treble – sing archaic words from a great distance. Although these intermezzos may appear to be unrelated to the external action, they do in fact reflect the essence of the situation in which the character, listening on his own, finds himself. In Wagner’s case we have a Minnesänger torn between his desire for sensual pleasure and his worship of the Virgin Mary, while Puccini’s artist, Mario Cavaradossi, expects that at sunrise he will lose not only his ideals but also his love for Floria Tosca and even his life. Here, too, the idyll is not only an oasis of innocence and a refuge from the world’s hurly-burly but also a harbinger of the disaster that is illustrated by the fate of a single person but which basically affects the whole of humankind.

The realm of the inexpressible

Music of the Romantic period: A journey to the depths of the soul

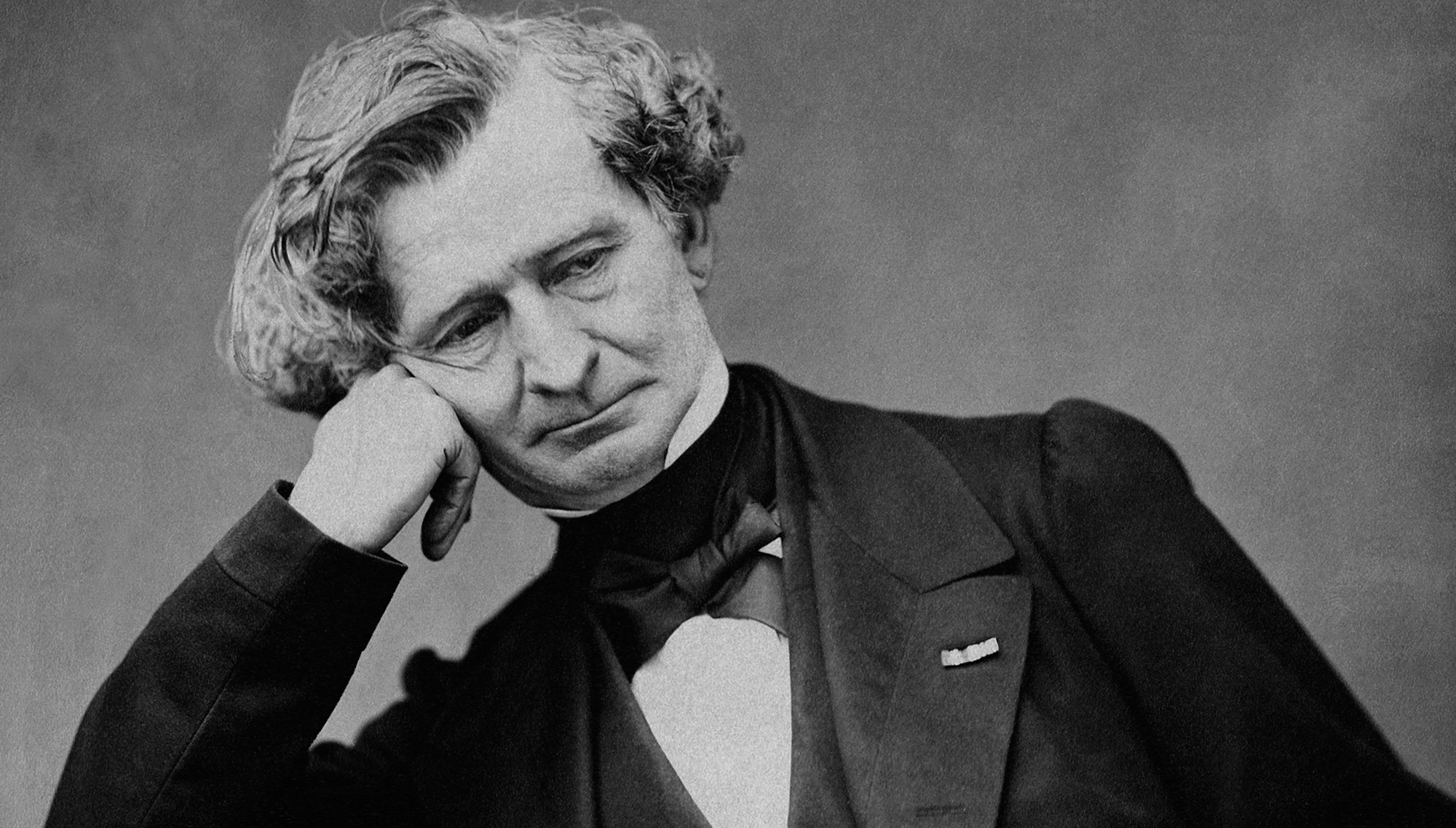

“A whole Beethoven in this Frenchman”

On the 150th anniversary of Hector Berlioz’s death

Biennale: “Paradise Lost?”

In February 2025, the Berliner Philharmoniker’s Biennale will focus on the threat to nature. A festival with concerts, guests from the world of science and much more.